Death and the dervish

B.M.Mihiz / E. Savin, after Meša Selimović’s novel

DERVISH AND A POET

In the midst of a picturesque and mythical milieu, concrete and symbolic, in the middle of this seemingly rationally organised imperial province and events provided with ideological, moral and psychological motivation, in the background or depth, you can feel intensive presence of a blurred essence, difficult to explain, from which the existence is separated. We are reached by hollow voices of a world which humanity hardly has the insight into. Presence of some irrational instigators and layers becomes more and more obvious. The power of words and understanding is weakened under the terror, violence, under the burst of bestiality and indifference which nature intercepts man with. Here where everything is wavering, the border between good and evil, deception and reality, truth and lie, language and matter, conscience and world, is also wavering. Prolonged into a typical oriental meditation and metaphysics, above which the spirit and the word of the Kurgan and Islamic philosophical tradition float, the world of certainty and law is disintegrating thanks to one real being filled with anxiety and fear, to be exposed as the reality of a nightmare, fate, coincidence. The world condensed into the metaphor of “running away and pursuing”, into the image of a dungeon whose foundations are cosmic and historical, could not motivate Ahmed Nurudin to believe in reason, but on the contrary, the suspicion that he himself was handed over into the hands of irrational, demonic powers which handle man and his destiny. The air of this great perplexity and inquiry are being breathed by all characters of Selimovic’s novel. While they talk, we have an inkling of what they are silent about. This procedure of leaving out, conveying through well-composed blanks is characteristic of Mesa Selimovic’s style and way of thinking. Mesa made a present of his contemplative temperament and his inclination towards philosophical to Ahmed Nurudin, placing him in the life circumstances which make such a man and such a contemplation feasible. Action and contemplation are permeated like literariness and viability, modelling that inner voice which is speaking. This dedication with which one talks cannot be brought down to the literalness. Dervish is guilty in his own eyes and he might become a hero, a traitor who might redeem himself, a judge who is his own judge and a witness, “a soul who scolds himself in a voice” intimate but not private, with irrelevant proportion of self-pity and intellectual affectation, in a refined but not lifeless voice, succulently but also subtly, with lucidity and experience, with restraint and at the same time with enthusiasm and elation, gentlemanly but not formally nor dreary. Death and the Dervish is a book of maturity, and the strength and force of its wisdom does not lie in the philosophical uniqueness of Nurudin’s deliberations, but in the poetic worthiness of the language, tone, suitable to the “mode of being” and its environment. What this book impresses by is not some isolated spectacular intelligence, but the sensibility and imagination of a poet on which this tragic vision of life leans on. Individual and solemn tone conquers, balanced and frenetic at the same time, the tone of a man who thinks about himself maturely and with profound.

From: Muharem Pervic Dervish and a poet (Selection of critical texts about Death and the Dervish in Miroslav Egeric “Death and the Dervish” by M.Selimovic Zavod za udzbenike i nastavna sredstva, Belgrade, 1995

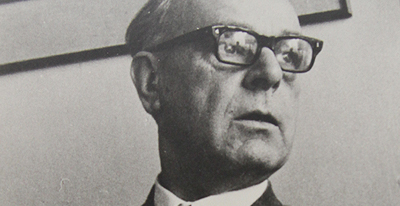

MEŠA (MEHMED) SELIMOVIĆ, writer

MEŠA (MEHMED) SELIMOVIĆ, writer

He was born on 26 April 1910 in Tuzla. He finished elementary and grammar school in his home town. He enrolled the Serbo-Croatian language and Yugoslav literature at the Faculty of Philosophy in Belgrade in 1930, and graduated in 1934. From 1935 till 1941 he worked as a teacher in civil school in Tuzla, and in 1936 he was appointed a trainee in the grammar school in Tuzla. The first two years of war he spent in Tuzla where he was arrested for collaboration with NOP (national liberation movement), in May of 1943 he crossed to the liberated territory, became a member of KPJ (communist party of Yugoslavia), and a member of Agitprop (propaganda office) for East Bosnia, and after that a commissar of Tuzla’s detachment. While in the partisan movement he married Desa Djordjic. His brother Sefkija was executed in 1944, and after that Mesa was transferred to Belgrade, as the head of the Department for publications of the Commission for determining occupied forces’ crimes. In June 1945 his daughter Slobodanka was born. In the summer of that same year he met Daroslava Darka Bozic, daughter of Zivorad Bozic, general of the former Yugoslav army, and he left his wife. “In August 1947 I was punished by expelling from the party, because although married, I was in contact with my present partner, and I hid it from the Party. I did not live well with my first wife, we did not get on well at all, and I fell deeply in love with my present partner. It would be normal to acknowledge that relationship and ask for a divorce. But as I was afraid of the impetuosity and unreasonableness of my first wife, I let the things unfold, hoping that somehow the solution would be found. Needless to say, the things only got more complicated, and my conduct towards the Party was dishonest, I was causing damage with my unworthy behaviour. The Party Unit of the Committee for culture, after revising the whole case, suggested I should be severely reprimanded. However, the Committee of the Federal Ministries expelled me from the Party – ‘because of my dishonesty towards the Party and the violation of the Party morale’, as Boro Perkovic, the secretary of my unit, told me. That just but hard punishment affected me deeply but at the same time helped me to get rid of many shortcomings I had...” By the decision of the Government of the Federative Republic of Yugoslavia, in 1947 he was transferred from Belgrade to Sarajevo (signed by the vice-president E.Kardelj) where he worked as the professor at the Teachers training college by the decision of Cvijetin Mijatovic, minister in the government of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The publishing house “Svjetlost” published his first book Offended Man. He married Darka in 1948 and they got daughter Masa. In 1949 he became a member of the Writers association of Bosnia and Herzegovina. That same year he got his third daughter, Jesenka, and once again became a Party member. “I am of the opinion that in those two years I was excluded from the Party, I had the attitude and the conduct of a communist, even though it was very difficult at times, because it seemed to me that I was discarded and forgotten. I was reinstated as a party member on 16 June 1949 in the basic party unit of the State publishing house “Svjetlost” in Sarajevo. I have a very good life with my partner (with whom I have two children), we love each other and get along fine. She is a good person and childishly naive. She is the daughter of a general of the former Yugoslav army; while she was still very young he married her to the captain of the former Yugoslav army, and as a war prisoner he stayed in Germany, but there are few traces of that former bourgeois background in her today. She is a member of the N.F. (the Popular Front) In my family Party members are brothers Muhamed, railway station master in Tuzla, and Teufik, assistant to the Interior Minister in Sarajevo, and sister Safija Ramadanovic, clerk in Tuzla...” He was chosen as the assistant professor at the newly founded Faculty of Philosophy in Sarajevo, but in 1953 he did not pass tenure review. “I was ........ I never found out why. I was without a job for four years, without any work and my family and I had a very difficult life...I did some odd jobs, which had nothing to do with literature, just to feed my family...” “Bosna-film” made some films based on his scripts: House on the Shore (directed by B.Kosanovic), Palm tree in the Snow (directed by R.Novakovic). There is a motto on the script for Palm trees in the Snow: “This film is dedicated to the Bosnian poets of the past centuries who were killed, imprisoned in towers, taken to the far away battlefields to die, as Hasan Kaimia, Ilhamija Zepca, Muhamed Nerkezi and others, about whom we know very little. If they could not see, in the darkness of their time, the light of our time, they were above their contemporaries by their belief in man and triumph of justice.” At the film festival in Pula he received a special recognition for the humane content of his script for the film Alien Country, based on his story and directed by Slovenian director Joze Gale. He was the art director of “Bosna-film” and drama director of the National Theatre in Sarajevo. At the beginning of 1959, together with Vlado Jablan he directed Tolstoy’s War and Peace (dramatization by Piscator, Neumann and Pripher). The performance incited great interest, and the most prominent actors took part: Boris Smoje, Milorad Margetic, Vladimir Jokanovic, Safet Pasalic, Liljana Sljapic, Olga Babic, Esad Kazazovic, and Reihan Demirdjic. That same year he was decorated with the Order of the Labour of the second order. He published his first novel Silences in 1961. With this book he finally attracted the attention of the Yugoslav literary public. That same year he became the editor-in-chief of “Svjetlost”, the leading publishing house in Bosnia and Herzegovina. At the beginning of the next year he was elected the President of the Writers’ Association of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Preoccupied with the theme of his lost and executed brother Sefkija, he started writing the novel Death and the Dervish two decades after the fact. “What am I now? Dwarfed brother or insecure dervish? Have I lost human love or have I harmed firmness of the faith, thus losing everything?...Have I lost human image or faith? Or both?” In “Oslobodjenje”, for the May Day, for the first time he published a fragment from his future novel Death and the Dervish. He had an intensive correspondence with Andric. That was the time of the heated arguments about the national issue and formation of the Muslim nation in Bosnia and Herzegovina. At the 7th Congress of the Writers’ Association of Yugoslavia in 1964 in Titograd, he was chosen for the president. He became close friend with Dobrica Cosic. “Prosveta” published the first book by Mesa Selimovic in Belgrade in 1965: the second edition of Silences. In magazine “Odjek” he announced that very soon he would give the manuscript of his new novel –Four Golden Birds (the primary title which he changed, influenced by Risto Trifkovic, to Death and the Dervish) to the publisher. In September 1966, “Svjetlost”, in the edition “Contemporaries”, published Death and the Dervish. “For too long I have been leading the life of a literary dervish-wanderer, to no one’s gain, and at my dispense...” He handed the manuscript of For and Against Vuk to Matica Srpska in 1967 and started writing The Fortress. The success of the novel Death and the Dervish did not abate. He received many awards. Town council of Novi Sad appointed him a member of the head committee of Sterija’s Theatre Festival (he would remain a member till 1981). The next year, The National Theatre in Zenica staged Death and the Dervish, dramatised and directed by Jovan Putnik. This event incited great interest of the Yugoslav public. Muffled conflicts with the political leadership of Bosnia and Herzegovina started, especially after Dobrica Cosic came to Sarajevo. In 1968 Cvijetin Mijatovic tried to persuade the writer not to leave Sarajevo. Collected Works of Jovan Ducic, which he edited together with Zika Stojkovic, was fiercely attacked in “Politika”. The harshest critic of all was Eli Finci. Mesa prepared his Collected Works which would be published by “Prosveta” and “Svjetlost”. Death and the Dervish was translated into 15 languages. In 1970 his Collected Works were published in Sarajevo. After some more statements, writings, pressures (polemic with Mladen Oljaca) he was thinking again about leaving Sarajevo. That was the period of his great fame. In June 1971 he got his first stroke. The second edition of The Collected Works was published. In June 1972 he retired and a new clash with his surroundings began. In the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Bosnia and Herzegovina (CK SK BiH) there was a meeting of the working group of the Central Committee, in order to “clarify some opinions” in connection with Mesa’s “refusal to accept the materials of the CK SK BIH” and Mesa’s “report at the meeting of the SK activists of the Serbian Literary Cooperative (SKZ) on 9 October”. “By defending myself from the ugly label of a nationalist, I defended the work of the SKZ, convinced that I was doing an honourable job. I said that the entire mood towards SKZ stemmed from the negative attitude towards one person, Dobrica Cosic, and it would be pity to undermine the work of an old cultural institution because of that”. He also wrote the lengthy letter to the secretariat of the CK SK BIH, which he ended with the words: “I am sorry to leave Bosnia with such a painful and gloomy feeling, because I was convinced that at the end it would be possible for me to have a more cheerful memory of my homeland. Writing about my profound consternation, I ask for nothing, not even somebody’s responsibility nor someone’s apology, all I want is to forget everything as soon as possible so that I can get rid of this feeling of a nightmare which is weighing down on me.” In March of 1973 in “Brusa –Bezistan” on Bascarcija, he said goodbye to his friends-writers: “I am leaving tonight and I will never come back...” He moved to Belgrade, and he was satisfied there. He only suffered because of the troubles his brother Teufik found himself in. To his nearest friends he said:” Read Kur’an, you will find all life wisdom there.” A film version of Death and the Dervish was made in 1974, in the joint production of “Avala film”, “Bosna film”, “Kosovo Film”, Film studio from Titograd, The centre of the film work communities Beograd and “Zeta film”, and it was directed by Zdravko Velimirovic. He had some conflicts with “Svjetlost” concerning publishing his books. In the National Theatre in Belgrade on 13 October, 1974, there was a literary matinee as was not seen in the capital, where the following writers read their works: I. Andric, M. Crnjanski, D. Matic, A.Vuco, M. Selimovic, B. Copic, V. Popa and S. Raickovic, and Petar Dzadzic gave the introductory speech. In 1975 TV Zagreb took off the programme in which Mesa Selimovic participated. “After a certain period of time director of TV Zagreb phoned me to explain that they had to take my programme off the air because TV Sarajevo threatened to switch off at that time and not because of the contents of the show, but because of my name (...) I suppose all that happened because my younger brother was on trial in Tuzla, because of the quilt that was unknown to me. But there is no collective guilt, so it is a nonsense that I should be on trial as well...” In 1975 Mesa underwent an operation at the military hospital because of the bleeding from the intestines. Following the publishing of some parts of Memories in December 1976, Fuad Muhic, professor of the University of Sarajevo and a member of the CK SK BIH, in “Borba” and “Oslobodjenje” published a series of articles entitled About one lamentation over the revolution; according to him, it was pretension to present personal tragedy as a tragedy of the revolution: “Firstly Selimovic laments over his own destiny. In the historical surroundings he was born in, everything conspired against him: from the tragedy of his brother to conscious hindering at the University, in the theatre, in cultural life, in spiritual creative work, till jeopardizing his existence...” And in Tuzla, his good acquaintances and admirers, commented well-intentionally: “Mesa exaggerates... He adds a lot, what is and what is not...” Mesa’s simply commented: “Politics is like a prayer, Politics is prayer... good for any occasion...And prayers are worth only as much...” In Belgrade, on 11 July 1982, soon after 10 p.m. on the eighth floor at 39 Jovanova Street, Mesa Selimovic died. He was honorary doctor of the University of Sarajevo (1971), member of ANUBIH and SANU (Bosnian and Serbian academy of art and science). He received many awards, among which the most significant are NIN’s Award (1967), Goran’s Award (1967), Njegos award ((1967), Award of the 27th of July of SRBIH, AVNOJ Award and others. His literary opus incorporates stories The First Platoon (1959), Alien Country (1957); novels: Silences (1961), Mist and Moonlight (1965), Death and the Dervish (1966), The Fortress (1970), The Island (1974); studies and essays: For and Against Vuk (1967), Essays and Reviews (1966), and autobiographical text Memories (1977).

B. Ilic according to: Radovan Popovic: The Life of Mesa Selimovic and www.znanje.org

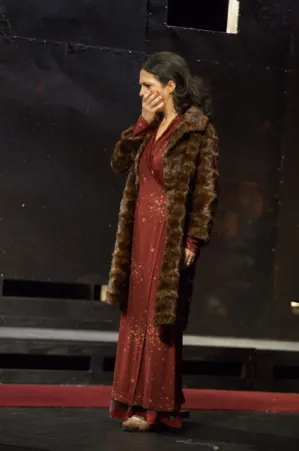

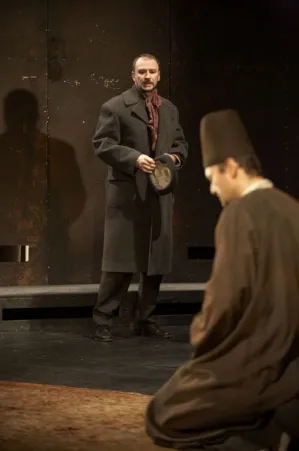

EGON SAVIN, director

EGON SAVIN, director

He is the professor of directing at the FDU in Belgrade and the FDU in Cetinje. So far he has directed 80 plays. The plays he staged had guest performances in Nancy, Paris, Warsaw, Tel Aviv, Vienna, New York... He is the recipient of a great number of awards. He tried his hand with success in almost all production models present in our country, from uninstitutinalized and experimental stages to almost all significant theatres of former Yugoslavia. With great success he stages the works of domestic and world classics in which he finds concrete clues which disclose the fundamental power of theatre in our times, and bind those plays and their authors to the concrete space and time. In the Belgrade National Theatre he directed Rostand’s comedy Cyrano de Bergerac (premiere on 22 March 1991), Sterija’s Scrooge (premiere on 25 December 1992), and Stuck-up Woman (premiere on 18 January 1998), than dramas Demon by Isaac Bashevis Singer (premiere on 15 March 2000) and A State of Shock by Sam Shepard (premiere on 26 October 2001).

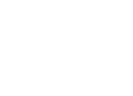

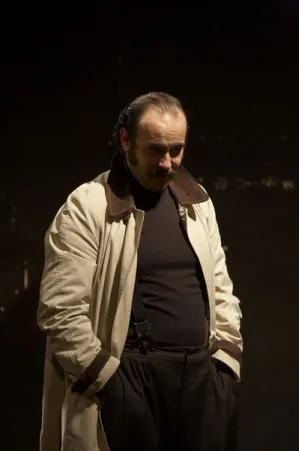

NIKOLA RISTANOVSKI, actor, a guest from Macedonia

NIKOLA RISTANOVSKI, actor, a guest from Macedonia

He was born in Ostrava (The Czech Republic). He graduated in 1993 from the Academy of the Dramatic Arts in Skopje, in Prof Vladimir Milcin class. He has been the leading actor of the Macedonian National Theatre since 1994. He played in about 2000 performances. Beside his theatre he also played in Skopje Drama Theatre, Montenegro National Theatre (Podgorica, Montenegro). Repertoire: Macedonian authors – Goran Stefanovski (Bacchanalia, Proud Flesh), Dejan Dukovski (Fuck it... who started first, Balkan is not Dead) and others; foreign authors – Shakespeare, Moliere, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov, Gorky, Gogol, Strindberg, Ionesco, B. Nusic (Questionable Person), Lj. Simovic. M. Krleza, Bond, D.Harms, D. Mamet, P. Marber, M. Ivaskevicius... awards: four times the award ”Vojdan Chernodrinski” for the best actor at the National Macedonian Festival, award at the Ohrid Summer Festival, at ISSTF (Rijeka, Croatia, twice), in Montenegro, at the MESS (Sarajevo, BiH); he also got the title “The Man of the Year”...

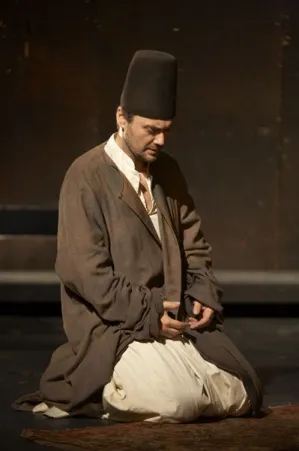

THE WORD OF A DRAMATURGE

For two decades Mesa Selimovic had been carrying deep inside the sorrow for the lost brother, before he turned it into the story about Ahmed Nurudin, dervish who, from the world of dogmatic principles enters into a changeable, unknown world in order to find out the truth about his arrested brother. Discovering repressive methods thanks to which the state authority operates, Nurudin gradually loses self-respect, and the pain for losing his brother is replaced with hatred and the wish for revenge. More than once, answering questions, Mesa Selimovic mentioned that hatred, envy, love and passion in general greatly influence man’s actions on conscious or unconscious level and that denying of all man’s currents – is denying of life itself. In his book about Selimovic’s novel, Miroslav Egeric notices that if something is of no use for value and richness of life of an idividual, it is of no use for life itself. Seeing the complexity of Nurudin’s character, we can only assume the drama that was going on inside the writer, while trying to understand the act of killing his innocent brother, but also to explain his own silence for such a long time. The performance adapted and directed by Egon Savin, points to the reasons for keeping silent, which was just a part of the deafening silence in the period when it was impossible to speak without consequences. The story was moved from the 18th century into the fifties of the last century, in post-war Sarajevo and new state. In a political system in which people sing about construction and freedom, one word can cost you your life, the moral responsibility of any individual, even dervish’s, can not been seen out of the context of power and state. Unfortunately, regardless of efforts and laws to protect rights and life of individuals in a modern world, we are the witnesses of the fact that Ahmed Nurudin could walk through our time, and would surely run into a close door, people who refuse to give answers, to dead silence and sneer, and he could even loose his life because of the spoken words. Thomas. J. Butler, in a text Literary stile and poetic function in the novel Death and the Dervish says: ”Dervish, at the deepest level, could represent a new myth of today’s life. According to this myth, eternal struggles, ideological frictions, nationalism and rage for power, destroy the structure of mankind to such an extent that people have lost the will for life, lost faith in each other. A man, who is being manipulated for political aims, in today’s time, feels the atrophy of natural instincts and dying out of the basic human emotions.” The only thing we do not know is whether Ahmed Nurudin would, in a moment of doubt, the last sentence “For death is senseless as is life”, say out loud or keep his mouth shut.

Branislava Ilić

Premiere performance

Premiere, December 27, 2008

Main Stage

B.M.Mihiz / E. Savin, after Meša Selimović’s novel

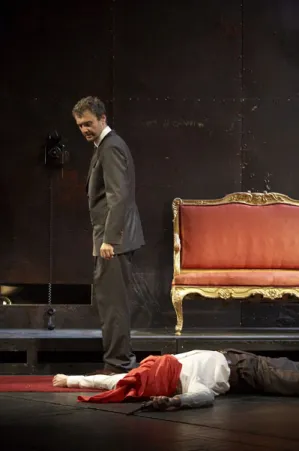

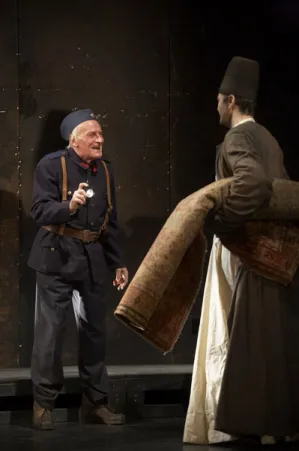

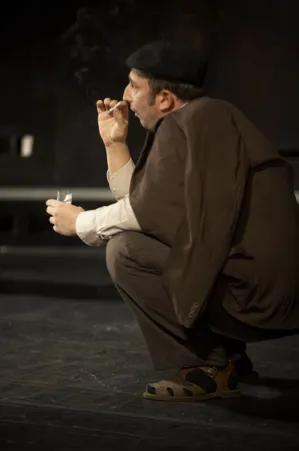

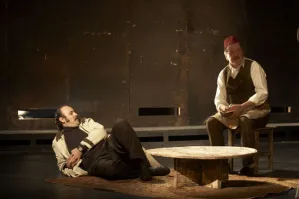

DEATH AND THE DERVISH

Based on dramatization by Borislava Mihajlovića Mihiza

Directed and adapted by Egon Savin

Premiere cast:

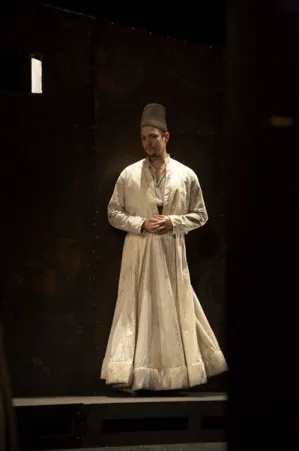

Ahmed Nurudin Nikola Ristanovski

Jusuf (Mula Jusuf) Nenad Stojmenović

Fugative-stranger Aleksandar Đurica

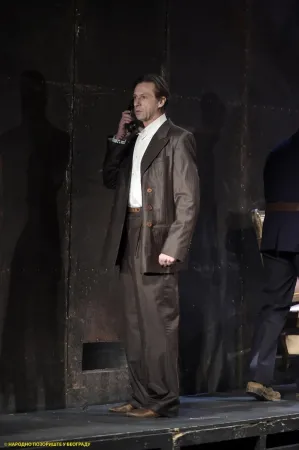

Judge’s wife (Cadi’s wife) Nataša Ninković

Hasan Dželebdžija Ljubomir Bandović

Inspektor (Muselim) Boris Pingović

Police officer (Spy) Zoran Ćosić

Judge (Cadi) Slobodan Beštić

Sinanudin (Hadži Sinanudin) Marko Nikolić

Jailor Nebojša Kundačina

Kara Zaim Tanasije Uzunović

Colonel Osman (Miralaj Osman Bey) Darko Tomović

Secretary (Vizier’s accountant) Miodrag Krivokapić

Young man Marko Janketić

Dervish Igor Ilić

Dervish (ballet dancer) Željko Grozdanović

Dervishes Aleksandar Vukić, Slaven Radovanović and Miloš Obrenović

Guards Milan Šavija and Miloš Dmitrović

Dramaturge Branislava Ilić

Idea for the setting Egon Savin

Costume designer Jelena Stokuća

Composer Zoran Hristić

Voice and dialect coach dr Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Décor realisation Milan Marković

Painting Srđan Pušeljić, Ilija Krković

Sound designer Zoran Jerković

Lighting designer Miodrag Milivojević

Assistant director Ana Grigorović

Assistant dramaturge Mila Mašović

Assistant costume designer Olga Mrđenović

Organiser Jasmina Urošević

Stage Manager Miloš Obrenović

Prompter Danica Stevanović

Mask making art Dragoljub Jeremić

Deputy stage manager Zoran Mirić

Sound technician Nebojša Kostić

Costume maker Drena Drinić and Radmila Marković

Shoe maker Milan Rakić

Sets made in the workshops of the National Theatre in Belgrade under the supervision of Svetislav Živković

Workshop coordinator Željko Rudić