The play of Hamlet in the village of Mrduša Donja

comedy by Ivo Brešan

ENOUGH FOR A LIFE

(Part of the interview “We are the thieves like all the others”, published in Zagreb’s daily “The Morning Journal” of September 7, 2005, which Adriana Piteša conducted with Ivo Brešan)

Writer and playwright Ivo Brešan (…) is an author of some of the most staged Croatian plays, including the famous one The Play of Hamlet in the Village of Mrduša Donja, as well as a great number of TV and film scenarios. Recently, however, “young and promising author”, as once described by Pavao Pavličić, devoted himself to writing of novels. “The Morning Journal” has published his latest novel The Three Lives of Tony Longin in its edition “Premiere”.

Although you are considered to be our greatest contemporary playwright, you don’t write plays anymore, but only novels. Why is it so?

Ivo Brešan: It is not a radical cut at all, as I used to write novels in those days when I was considered to be primarily a playwright. But the fact is that I’ve stopped working on plays in a certain moment. Indeed, with the style of mine, I can hardly fit into the contemporary trends prevailing in nowadays theatre, in which there is generally less and less dramatic literature. In nowadays performances even the text is not required, actors improvise, and in the case of classical text everything is turned up to the extent that even the author cannot recognize his own text. However, if the literature is in theatre focus then it is a prose, for example a novel is adapted for the theatre needs. Thus I asked myself was there a sense in writing the plays and wasting the ideas, if nobody would read or stage them ever. So I thought that the best thing was to return to prose, with which I had started. And the second reason was my age. Playwright is very demanding, and very limited considering its means of expression, because apart from dialogues and didascalias there are no other means. Besides you should treat the subject equally as you do it by novel. Furthermore, as I am getting older I am more and more inclined to thoughts, to philosophy which is acceptable for prose, but not for drama. If characters start to express their opinion at stage, the play is ended; the performance is failed. All my novels, especially those written recently, are essentially derived from philosophic ideas. Sure, they were also relevant elements of my plays, but here they are more explicit and clear. Certainly, I am not farewelled to drama, but I have twenty-three plays behind myself, which is quite enough for a life.

Do you miss a direct insight into a public reaction on your work, which you normally had, in case of your plays?

Public reaction is something that is very distrustful. For all those years I have learned that people very often applaud at the performance, and then after it say that it was a real bullshit. That’s why I am never sure when people come to congratulate after the performance weather they are doing it sincerely or just for the convention. However, the same could be applied on critics, for they are all people of different taste, priorities, thoughts… What’s more, Hamlet in Mrduša Donja was not positively received by everyone, and not only for its political component.

Humor was a special brand of yours. You have left drama, but if judging by your novels, why have you left humor also?

I have always understood humor in a special way. My idea has never been just to make people laugh, but to make them to think and to free themselves through the laugh. When people went to see Hamlet in Mrduša Donja they laughed, but not at comical turnovers only. In fact, they laughed at the situation that they listened to the words that were not spoken on the street, because they were forbidden. If that element is missing, then humor is narrowed to an ordinary joke. Our today’s reality doesn’t provide material for such type of humor. It is acceptable to laugh at events, at persons, but everything stay within the limits of daily satire and joke, which is not my field of interest.(…)

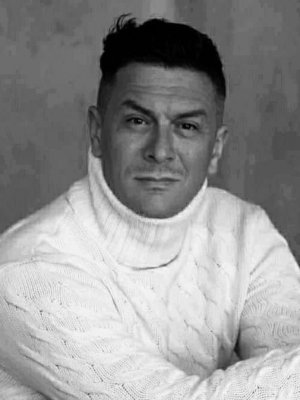

ŽELIMIR OREŠKOVIĆ

ŽELIMIR OREŠKOVIĆ

Želimir Orešković was born in Zagreb, where he finished high school and graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy. He also graduated theater directing from the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade, in the class of professor Hugo Klajn. He received his MA degree in Warszawa. He was engaged on a permanent basis in the theatres of: Tuzla, Mostar, Sarajevo, Novi Sad, Beograd and Zagreb. He has received many significant awards, such as: “Bojan Stupica” Award, MESS “Golden Wreath” Award, “Marulović days” Award, Award of the Association of Croatian Actors, Maribor Festival Award, “Golden Turkey” Award for the best performance at the festival “Days of Comedies” in Jagodina, “Judita” Award at the Summer Festival in Split, etc. Premieres at the stages of the National Theatre in Belgrade: Hasan-Aga’s Wife by Ljubomir Simović (1974 – the first stage setting ever), Constructor Solnes by H. Ibsen (1975), one-act plays Protest by V. Havel and Attest by P. Kohout (1984 – “The Circle 101” Stage), Mary Magdalene and Apostles after the Last Supper (1987- Zemun Stage). Up to now, he has directed more than 170 performances. He lives and works in Zagreb.

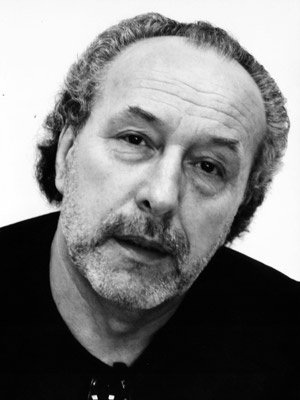

IVO BREŠAN

IVO BREŠAN

Ivo Brešan was born in Vodice. He attended high school in Šibenik, and graduated from the Faculty of Philology in Zagreb, Department of Yugoslav languages and literatures. After finishing his studies, he was engaged as a professor in the high school of Šibenik. Since 1983 he has been an artistic director of the Croatian Cultural Centre and the International Children’s Festival in Šibenik. His first playwright The Four Ground Rivers was printed in 1970, in the literary magazine “Vidik”, published in Split. After five years of ineffective endeavor to find a theater willing to stage his play, he finally succeeded, in 1971: the ITD Theater in Zagreb put on its repertoire his grotesque tragedy The Play of Hamlet in the Village of Mrduša Donja, directed by Božidar Violić. After the premiere, the play has been staged in almost all the theatres throughout the country as well as outside the country, in: Poland, Austria, Germany, USSR, Bulgaria, and Sweden. He has written twenty-three plays, among which, besides The Play of Hamlet in the Village of Mrduša Donja, the most popular are: The Icy Seed, Nihilist from Vela Malka, The Sunken Bells, The Nit, Devil at the Faculty of Philosophy, The Death of a President of the Tenants Board, Festive Dinner at the Mortuary Company, Appearance of Jesus Christ in the Military Barrack PO. Box 2507, Archaeological Diggings near the Village Dilj, Anera, Hydro Plant in Suhi dol…. He has written eight novels: The Heaven Birds (TV serial was made after it), Confessions of Characterless Man, Astaroth, God’s State 2053, Gambling with the Destiny, The Devil’s Entrails, Gorgons, The Three Lives of Tony Longin, as well as a collection of tales The Cracks. In cooperation with Krsto Papić, a director, he has written scenarios for the following films: The Play of Hamlet in the Village of Mrduša Donja, The Rescuer, and A Secret of Nikola Tesla. In cooperation with Veljko Bulajić he has written scenarios for the films The Promised Land and The Donator, and in cooperation with Vinko Brešan scenarios for the films How did the War begin at the Small Island and The Marshal. Since 2002 he has been retired. He lives in Šibenik.

PRIMITIVISM IS THE GIST OF THE WHOLE BALKANS

(Part of the interview published in the “Pozorisne novine” no.11, November 2006, which Mikojan Bezbradica conducted with Željko Orešković)

(...) You staged this play very successfully for the first time in the middle of seventies in Novi Sad. What was your motive to redo it after a time-gap of more than thirty years?

It is a proved, almost classical text of Croatian literature, which was performed also outside Croatia. It has its history, but is still very vital. When the management of the National Theatre decided to put on repertoire a Croatian play, I suggested some other texts also, but they found that none of them would be appropriate enough for their requirements and chose Hamlet in Mrduša Donja. Truly, reading of this text today is equally exciting as it used to be in 1971, when it was staged for the first time. Certainly, it is not as exciting as it was considering social context when it was received as a real bomb tampered under the communist regime in Yugoslavia, but in any case the text still retains, even nowadays, well I may say, a kind of parabola: you aim somewhere high, but get somewhere low. Thus, there is a good reason to work on it again, but in a way not to revise or update anything. One of the set elements of the first setting was the picture of Josip Broz Tito, President of our ex-state, Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. We have staged that play in a hall, at the old stage of the Serbian National Theatre, which was designed as the Culture Centre. Since we have played it on at proscenium, exactly above the place reserved for orchestra, we have to cover the hole with boards. But in a round dance scene, with lots of people, the boards started to vibrate and consequently everything began to tremble. As a round dance symbolizes the culmination of primitivism that upsets all of us sooner or later, I have persuaded a decorator to loosen the nail and naturally Tito’ s picture immediately fell down on a floor. It happened at the preview. The next day, at the premiere, the police surrounded the place.

They have stood there and the picture of course has never fallen down again. From today’s point of view, what symbolism can be found in all of that?

The picture of comrade Tito has fallen, but in a very horrible way. Its fall has caused a lot of human disasters. Perhaps Yugoslavia could have been disintegrated in a somewhat different way, as it was the case with Czech Republic and Slovakia. However, the fall of that picture caused great quakes and I think that the way in which Yugoslavia has been disintegrated is perceived in the main idea of this piece. To be precise, a character in drama says that the life’s key principle is: “In, on and under myself”. To conclude, that awful primitivism implied in these three replicas is, unfortunately, the gist of this region. Which region do you mean? The Balkans, the whole Balkans. I still think of Yugoslavia as a whole. Unfortunately, in these regions, whatever ideology prevail it will acquire the most primitive features. At the end of the drama, there is a round dance, almost anthological, and it is sung in the decasyllable. All verbs in it are of negative connotation: drink like an animal, shit on all, piss on all. The verbs preferred reflect a complete destruction. It seems that in these regions our intention is really to destroy everything. Therefore, the elements that could be normally disassembled are disassembled with destruction. Whatever we think of it and whatever we wish to think, Yugoslavia used to display certain level of civilization, which was drastically ruined in 1991. Now we shall undoubtedly need quite a time to re-establish that civilization level again. And I think that we can discover this parabola of Brešan in a fact that we refuse to identify that destruction within ourselves. Brešan enters very wisely and very witty into a dialogue with canons of Western theatre and its most outstanding revenge tragedy – Hamlet by William Shakespeare. On the other hand he is full of explicit allusions on daily politics, flavoured with black humour and sharp satire. You have already mentioned that the first performance of The Play of Hamlet in the Village of Mrduša Donja held on April 19, 1971 at Zagreb’s ITD Theatre, caused a real shock within socialist society. What are the elements that can “move from a chair” a Serbian theatregoer, now, after thirty years, in the era of transition? First of all, I think on a kind of primitivism that, regrettably, always takes its opportunity. To be more clear, the layer of civilization around us is very thin and each time when it is attacked by primitivism, it simply perishes. As a rule, then follows the tragedy, which could have been avoided. In these latest events nobody achieves his aims, but nevertheless we have all paid dreadful price. Do you think on war waged on the territories of ex Yugoslavia? Yes. None of the side involved has obtained its optimal aims, but damages were really optimal and the most terrible at all the sides. As it represents universal metaphor of primitivism, nonsense and narrowness of every totalitarian regime, this piece was excellently received in many states located on the other side of the ”Iron Curtain”.

Is it possible that such “global metaphors” are recognized even today after the fall of “Berlin Wall” and everything that followed it?

Certainly. This performance is immanently comical. It has also been staged in the West, although they are not so sensitive on our political metaphors. Imagine that, some peasants want to make Hamlet! But it is a big bite for them. They are so comical in their way of simplifying Hamlet. That is a pure comedy. It could have also been comedy dell’ arte. It is a well-known situation: somebody wants to proclaim the minor for the major. What suits to Jupiter, doesn’t suit to ox. The plot is based on this principle and that is a pure comedy, I’m talking about. However, at the end there is a turnover, manifested in the parallel story of Hamlet, which takes place in a real life of Mrduša Donja.

Brešan wrote that it was a tragic grotesque, didn’t he?

Exactly. He perceived that text as a tragedy, but for a long time we have treated it as a comedy. Actually, it is extremely funny, and I hope that we shall manage to repeat that humour at the stage. Many theatre people have said, using the sports terms, that your A-league cast list presents the real “dream team” of actors, because it gathers artists such as Marija Vicković, Nela Mihailović, and Bane Tomašević of younger generation, then Vladan Gajović and Branko Vidaković of middle generation and finally Miodrag Krivokapić, Predrag Ejdus and Marko Nikolić of elder generation. I have been Belgradian for twenty years, so I am well informed about professional activities of Peca Ejdus, Marko Nikolić and Bane Vidaković. Also, Brik Krivokapić is a friend of mine from our Zagreb days. Architecture of this piece is built on eight characters, and I have personally insisted to work with four or five of them, while the others have been recommended to me. As I can see they are also media stars. Owing the circumstances, now I have opportunity to see more performances of the National Theatre and I can say that their ensemble is really a good one. If I had made another selection, I am sure, it would have also been of a top quality. In the last years (it was impossible at the time when The Play of Hamlet in the Village of Mrduša Donja was written, or maybe I am wrong?) it became practice to translate some plays, books, and movies from Serbian to Croatian language and vice versa. You haven’t joined that practice and decided to stage the play in its original dialect? It is a very complicated question and frankly speaking, I am not a linguist, although I graduated from a Linguistic Faculty in Zagreb… As you know, it was a political decision made in the middle of 19th century, the so-called Vienna Agreement of 1850 that declared common literary language for the area. During last 150 years the general tendency was to accept that language as a common one. However, it hasn’t become common. Now there is a tendency to separate it again, but most of the people understand both of them. Mr. Brešan has identified in this play a wonderful idiom of the Dalmatian province. It is of stokavian dialect, but of ikavian pronunciation. It is the same dialect as yours, but has its original local pronunciation, although there is no difference in pronunciation of vowels. It is absolutely understandable for everyone. In fact, it presents a kind of unusual, peasant speech. As soon as we hear that speech at the stage, we know that certain kind of primitivism must be involved. If we tried to transform it, we ought to have done it in a way that it become let’s say, a dialect of Vlasotina, or some other Serbian dialect which would immediately give us an idea that we are far away from the centre, in a very rural setting. But, I didn’t want that, as the speech is completely understandable. For comparison, there was an attempt in Croatia to translate Serbian films, for some political reasons. However, they had only one projection with such a caption and it generated roaring laugh in the audience. So they gave up that practice. Brešan’s play is deeply drawn in long ago past times of rigid and strict norms and codes.

Is it possible that the change of social system initiates modification of mental constitution?

Unfortunately, the change didn’t modify mental constitution. You know, I am afraid that politicians are recruited from the worst people living in these regions and that those of attitude and reputation never enter such groups. It seems that politics is always tending to recruit the worst staff within itself. But, take this with reserve. For long ago, precisely from Aristotle the politics was ranged very high, but everything that has happened during last 100 or 150 years contradict such concepts. They were not the best who had a power to decide upon the vital interests of those nations… It means that Bukara and his companions are, unfortunately, still our contemporaries? Exactly. What is the power of art and artists to prevent such circumstances? No actor or man of art could have ever prevented such circumstances. All artists who have joined the politics have managed only to risk their reputation. Unfortunately, art is something that is incompatible with politics. Every artist, at the end, gets out of the politics ruined and dirtied …it is not a lucky combination - art and politics. We, people of art, have had great pretensions to change something. But we haven’t managed to change anything, nor ever shall we.

You sound very pessimistic?

Nobody cares for artists’ opinion. We are usually blamed for many things, but in fact our influence is very weak. If somebody had listened to artists and intellectuals, those things would have never happened. You know, there is an old proverb saying: “When cannons begin to thunder, muses become silent”. And that’s true. When cannons began to thunder, muses really became silent…

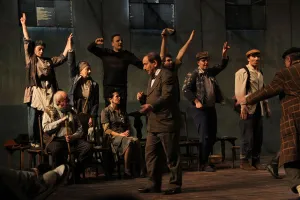

Premiere performance

Premiere, January 30, 2007 / "Raša Plaović" Stage

Director Želimir Orašković

Dramaturgue Zoran Raičević

Set Designer Boris Maksimović

Costume Designer Marina Vukasović Medenica

Composer Mihailo Blam

Stage Speech Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Stage Movement Ivica Klemenc

Corepetitor Mirjana Drobac

Organiser Nemanja Ralić

Stage Manager Saša Tanasković

Prompter Gordana Perovski

Lighting Designer Nait Ilijazi

Make-up Designer Dragoljub Jeremić

Stage Master Dimitrije Radinović

Sound Designer Uglješa Radonjić

Premiere cast:

Mate Bukarica, called Bukara, a director of the Collective Farm and a secretary of the Party’s Regional Section, in role of king Claudius Miodrag Krivokapić

Mile Puljiza, called Puljo, a president of the Regional Section of the People’s Front, in role of Polonius Branko Vidaković

Anđa, his daughter, in role of Ophelia Marija Vicković

Mara Miš, called Majkača, a village innkeeper, in role of queen Gertrude Nela Mihailović

Mačak, a president of the Collective Farm Board of Directors, in role of Laertes Vladan Gajović

Joco Škokić, called Škoko, a village guy, in role of Hamlet Branislav Tomašević

Andre Škunca, a village teacher, as a director of the play Predrag Ejdus

Šimurina, a commentator and an explainer of the play Marko Nikolić

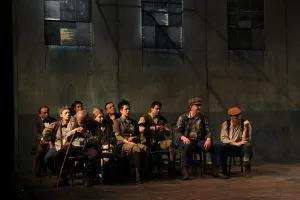

Other peasants of Mrduša Donja Gorjana Janjić, Ognjanka Ognjanović, Srboljub Milin, Mida Stevanović, Slaviša Čurović,Uroš Urošević, Zoran Maksić, Bojan Serafimović, Đorđe Usanović*, Aleksandar Danojlić*

Costumes and set were manufactured in the workshops of The National Theatre in Belgrade

* Members of the Artistic Association “Lola”