Volume two

drama Branislav Nušić

ABOUT THE PLAY

According to Borivoje Jevtić, one of the reasons Nušić decided to accept the “unrewarding and distressing” function of a theatre manager once more at the age of sixty-one, this time in the Sarajevo theatre, and to “leave his beloved home town, Belgrade”, was his deep dissatisfaction with the Serbian Royal Academy of Sciences and Art, since the Academy failed to nominate him for membership in 1924. “The public was not aware of the fact that he was not even formally nominated. Still, it seems that this fact was the most painful moment for the great comedy playwright. Nonetheless, the situation had a positive effect in the long run (from today’s point of view). Seeing that he had not been nominated and being informed by his friends about the issues the Academy held against him (…), he adopted a more serious perspective about his work. Instead of merely looking for comical situations and making people laugh, he started looking for opportunities to criticise and expose matters in his plays”, claims Siniša Paunović. Paunović obviously has in mind the last decade of Nušić’s life, from his return from Sarajevo (1928) until his death (1938), a decade when he wrote The Cabinet Minister’s Wife, Mr. Dollar, The Bereaved Family, Dr. and The Deceased. Therefore, Paunović, as well as most critics and theatre theorists, completely disregards the Sarajevo period of Nušić’s life (February 1925 – April 1928), although he wrote seven plays in this period – according to the chronological list of his plays, which Nušić himself made. In 1926, he wrote four “small scenes” The Fly, Button, Rent Free and The Mouse; while in 1927, he wrote the play Volume Two, “dramatic fairytale” Eternity and comedy Dangerous Game. However, one should say that the three texts from 1927 – out of the three, only Volume Two was produced in the Sarajevo theatre, directed by the author – are not similar to the rest of Nušić’s opus and this is probably why the reviews and theatre studies have disregarded it as a rule. Deviation from the playwright’s practice was not accidental, it seems that it was his answer to the statement by “the immortals” that he was not an “academic figure”. Furthermore, in a letter to his daughter (Gita Nušić-Predić) where he wrote about his unfulfilled hopes to become a member of the Academy, Nušić explains his “academic failure” in the following way, “My tragic problem lies mainly in the fact that I am a comedy writer. Comedy writers of all nations have always been bitterly underestimated, regardless of their successes.” (…) Therefore, the fact that he did not make it into the Academy was so distressing for him that he wrote in a letter to his daughter about the tragedy, caused “mostly” by the facts that he is a comedy playwright, and about how people easily “succumb to prejudice that humour is a synonym for lack of seriousness.” (…)

However, his creative inspiration was still strong even at his older age. “In the moment when I write a story”, Nušić writes to his daughter in the letter, “there are five or six other motifs fighting for my attention; but when I write a comedy, there are five or six full, and completely finalised summaries in my mind, they queue, fuss and demand to be accepted.” Therefore, wouldn’t it be logical to assume that in his Sarajevo period, obsessed by the thought that he could not expect much as a comedy playwright, he deliberately dedicated his creative effort to a different literature orientation, which irresistibly reminds us of the so called magical realism. (…)

In Volume Two, Nušić had no intention to be a comedian, instead he “overwhelmed by doubt and dissatisfaction” reached for bizarre stories in which love has a significant role. (…) He introduced “the world of absurd and intellectual play” into his literature, which made him closer to the magic realism or, as Niko Bartulović would say, the “new romanticism”. Although Nušić did not believe, as some of magic realists did, that the whole reality is encompassed in magic, his “starting point” in Volume Two is – mystical. (…) A bizarre case gravitating towards mysticism is a result in the structure of Nušić’s play Volume Two.

Predrag Lazarević, Nušić and the Magic Realism

Volume Two has a special place amongst plays Nušić wrote during his stay in Sarajevo. It is a play in three acts, performed for the first time in the National Theatre in Sarajevo on 26th October 1927; it is also a piece produced only once more, after the playwright’s death, in the occupied Belgrade in 1942. The play did not have much success on stage, although the announcements for the first performance in Sarajevo indicated important thematic and dramaturgic novelties. What are the novelties Nušić introduced with the play Volume Two in our dramaturgy of the 1920s? – Was it its original form, or an ambience in which the plot takes place? Or, was it, perhaps, the theme, which could be defined as a representation of a fatal impossibility to fight one’s own destiny, attributed to the lead character by an accidentally formed irrational idea? – Doubtlessly, there are novelties in everything listed here. Although there were pieces that dealt with life behind the stage before Nušić’s Volume Two, none of these portrayed actors and their preoccupations, as well as their interpersonal relationships in private lives as widely as this play. Similar to Eugene Scribe in his famous Adriana Lecouvreur, Nušić devoted himself to portray the life behind the stage, though without romantic sentimentality. One would even say that he wanted to be modern while treating a dramatically fruitful theme. It is obvious that Nušić was somewhat inspired with Pirandellian theatre, which is not so strange since Pirandello was very popular in our theatres at the time, and provoked various reactions with both theatregoers and performers. Therefore, we can assume that the fact Pirandello was so popular in our theatre may have inspired Nušić to write Volume Two. (…)

However, while Pirandello does not recognise reality and believes art is real, on the one hand, Nušić, on the other, seems to look for a compromise: he sees elements that belong to art, namely – to the theatre, in the real world. In addition, he can distinguish between life and literature – characters and their situations, but he also believes that a normal life can be portrayed in a book, in drama literature. Thus, he distances himself from Pirandello, but he also comes closer in the manner of observation of life-like performance, life-like theatre. (…)

This is how he brought to life the magic world of “talents and admirers” successfully; let us use Ostrovsky’s inventive phrase. In the process, Nušić expressed his undeniable knowledge about the people, as well as his lucidity in portraying their manners. However, one question is inevitable; did Nušić introduce himself into the play by introducing the character of Playwright? There are many reasons for the question; although we are not aware of the plot of the play Playwright finishes reading at the beginning of Volume Two. However, we could deduce from the very end of the play Playwright reads, that it is about a theme Nušić wrote in other plays (It Had to Be That Way, The High Sea). In addition, certain comments by critics from the first act of Volume Two resemble the comments given to these plays, while Playwright’s answer is almost identical to Nušić’s account regarding a situation when after the premiere a lady wrote to him in order to express her gratitude to him for not using her name in the text, because she had experienced identical situation in real life! (…)

Volume Two is especially important because, in a certain manner, it announces Nušić’s creative process in his most significant comedy, The Deceased, regardless of thematic dissimilarity between the two plays. Life and art, fiction and reality become intertwined in such an obvious manner, but also in Pirandellian tone, in Nušić’s theatre.

Raško V. Jovanović, Volume Two

ADVENTURERS FROM “THE GREAT THEATRE”

When a person thinks about Branislav Nušić’s work (I guess there are such people), the first association are comedies in which the playwright turned life situations into drama adorned with social and political arabesques. Frequently overlooked fact is that complexity of Nušić’s work is not exclusively linked with perfectly tailored comedies (frequently produced in Serbian theatres), but also with exploration and disclosure of his works which have been hardly ever or never produced and performed on stage. In them, there are no cabinet minister’s wives, parliamentarians, district spies, dull-witted chiefs of police or bereaved families. However, there are few suspicious persons and, maybe, few deceased people…

The writer’s approach, or shall we say his style when writing the “neglected” pieces, is significantly different from everything we might expect from him, to such an extent that only a few people could firmly state that Ben Akiba is the man who wrote those pieces. In them, there is a divergence from analysis of characteristic flaws of character, salons and summerhouses replace small towns and remote places, witty comments easily associated to daily politics are replaced with Shavian-like humour, melodramatic line is enhanced, focus is shifted to higher classes or artistically inclined classes of society…

In this regard – Volume Two is probably the best example of Nušić’s “forgotten” plays. It could be because it seemed that this skilfully designed story possesses too much of drama, which could be more suitable to European (Ibsenian?) analysis of society then to Nušić’s humorous scrutiny of “little” people who experience unsolvable problems (hand in hand with those in power). Characters in Volume Two live their secrets without obstacles, they play roulette without an idea how much their “indifference” may cost them. Nušić takes both his characters and audiences into Thespis’s cart, as if they are all on a short tour through the world of theatre, until the moment when the things that seem obvious become curious, i.e. until the moment when elements of destiny, together with a dose of mysticism, result in a crime. If we accept the basic definition by Philip Core that “camp is the lie that tells the truth”, all characters from Volume Two walk in that minefield: actors mix real with the interpreted emotions, Playwright takes stories from reality in order to protect himself from it, and critics believe in objective truth while they taunt by claiming the opposite…

There is no reason to doubt that the artistic world from Nušić’s time actually resembled the one the writer portrayed. “Peeping through a keyhole” is still peeping through a keyhole today. A constant. Only the manners are changed in contemporary popularisation of standards. A wish to create art has been replaced with compulsive tendency to attract attention, while keeping distance between private and public became an outdated category – equal to social suicide. Media even openly state that this is a model to live by. We progress the wrong way. This is how the world we live in is organised.

Slobodan Obradović

ANĐELKA NIKOLIĆ was born in Smederevska Palanka in 1977. She graduated from the Department of French Language and Literature at the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade, and at the Department of Theatre and Radio Directing at the Faculty of Performance Arts in Belgrade. Nikolić has directed productions by classical authors (Brecht, Beckett, Sophocles, Voltaire, Shakespeare, Gogol, Krleža, Vojnović, Marinković, J.S.Popović, A.Lindgren), as well as by modern playwrights (J. L. Lagarce, M. Crimp, Milan Marković, Simona Semenich, Olga Dimitrijević). She has worked in theatres in Subotica, Kikinda, Novi Sad, Ljubljana, Celje and Belgrade (Little Theatre “Duško Radović”, Bitef Theatre, Atelier 212, Yugoslav Drama Theatre). Nikolić has participated in the following festivals: Sterijino Pozorje, Festival of Professional Theatres of Vojvodina, Bitef Showcase, Comedy Days, Teden Slovenske Drame, Festival Borštnik Gathering (accompanying programme), Die Besten aus dem Osten/Slowenien. She is the recipient of the award for directing at the Festival of Classics in Vršac (German Shepherd), at the Small Scene Theatre Festival in Kikinda and in Sterijino Pozorje Festival (Workers Die Singing, the production was awarded with seven Sterija Awards). Her production of Pippi Longstocking was proclaimed best production at Pika’s Festival in Velenje. As part of the art group Hop.la!, which she co-founded, she realizes independent artistic projects and events (On Violence, Short History of Forgetfulness, On the Spot, Down the Sava River in Summer, Shakespeare in Park, Action for Children). She translates, mostly plays, from French and English languages. She lives in Belgrade.

ANĐELKA NIKOLIĆ was born in Smederevska Palanka in 1977. She graduated from the Department of French Language and Literature at the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade, and at the Department of Theatre and Radio Directing at the Faculty of Performance Arts in Belgrade. Nikolić has directed productions by classical authors (Brecht, Beckett, Sophocles, Voltaire, Shakespeare, Gogol, Krleža, Vojnović, Marinković, J.S.Popović, A.Lindgren), as well as by modern playwrights (J. L. Lagarce, M. Crimp, Milan Marković, Simona Semenich, Olga Dimitrijević). She has worked in theatres in Subotica, Kikinda, Novi Sad, Ljubljana, Celje and Belgrade (Little Theatre “Duško Radović”, Bitef Theatre, Atelier 212, Yugoslav Drama Theatre). Nikolić has participated in the following festivals: Sterijino Pozorje, Festival of Professional Theatres of Vojvodina, Bitef Showcase, Comedy Days, Teden Slovenske Drame, Festival Borštnik Gathering (accompanying programme), Die Besten aus dem Osten/Slowenien. She is the recipient of the award for directing at the Festival of Classics in Vršac (German Shepherd), at the Small Scene Theatre Festival in Kikinda and in Sterijino Pozorje Festival (Workers Die Singing, the production was awarded with seven Sterija Awards). Her production of Pippi Longstocking was proclaimed best production at Pika’s Festival in Velenje. As part of the art group Hop.la!, which she co-founded, she realizes independent artistic projects and events (On Violence, Short History of Forgetfulness, On the Spot, Down the Sava River in Summer, Shakespeare in Park, Action for Children). She translates, mostly plays, from French and English languages. She lives in Belgrade.

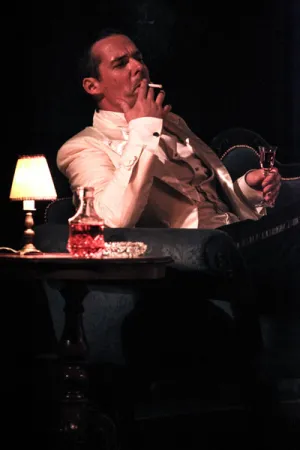

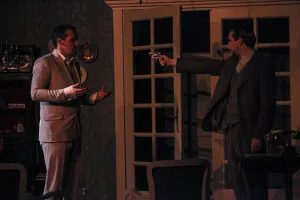

LITERATURE AS A SCENE OF CRIME

At the beginning of the play, in a crowded room, a man declares that he will kill a woman. In the end, the very thing happens. What happens in the meantime is the non-prevention of such an act. Nobody does anything to prevent it, neither the murderer to be, nor the future victim, nor the witnesses to the murder announcement, nor the people who are present when the violence progresses - nobody. In Volume Two, there is a lot of talk about love, just like in another play which ends in vicious murder: Othello by Shakespeare. And yet, this is not a play about love. This is a play about a special type of violence, still socially acceptable and prone to be considered romantic – about the so-called crime of passion. “Lust murder” was a popular motif in European art, film and literature between the two wars. Some people consider that artists, who came back from the front, shifted the focus of aggression from war to “peacetime” enemy – a woman, and that the mutilated bodies on canvasses were a reflection of war traumas. Others say that the obsession with murderers of children and women was a sign of decadence in a society facing Nazism. We do not know who was it that Nušić wanted to kill symbolically. He was already a popular writer when he wrote a piece that ends in a brutal murder of the National Theatre’s diva. Anyhow, Volume Two sends out certain contempt, even rage against both artists and women. Rajna Maretić Dolska, famous tragedy actress, who gets murdered by a jealous admirer, is a fresh character in the gallery of female characters created by Nušić, which consists of “upstart harpies, ingratiating and stupid wives, immature girls who dream of ideal suitors, adulterers who commit suicide out of shame or lose their children as a sort of punishment for their immoral behaviour, caricature of vulgar personalities”… The list is a result of our ad hoc research, but it would be very interesting to take on a more detailed research on the subject and to cast a new light to the work of Branislav Nušić by analysing ideological patterns it possesses, both in comedy and in melodrama. Since, in the year of jubilee, Nušić is more present than ever. So is the rule of patriarchate.

Anđelka Nikolić

Premiere performance

Premiere 20th October 2014 / "Raša Plaović" Stage

Director Anđelka Nikolić

Dramaturge Slobodan Obradović

Set Designer Vesna Popović

Costume Designer Olga Mrđenović

Music Composer Draško Adžić

Stage Speech Dijana Marojević Diklić

Stage Movement Bojana Mišić

Sound Design Vladimir Petričević

Recorded music:

Dušica Mladenović, violin

Boris Brezovac, viola

Aleksandar Latković, violoncello

Dobrivoje Milijanović, recording

Premiere cast:

Rajna Maretić-Dolska, a drama actress Nela Mihailović

Ida Podgorska, a drama soubrette Zlatija Ivanović

Mira, a novice in acting trained by Rajna Marija Bergam

Ivan Ivanović Dušan Matejić

Lover Srđan Karanović

Mr. Teodor Gojko Baletić

Playwright Bojan Krivokapić

Editor of The Comedy Magazine Andreja Maričić

Critic of The New Horizon Review Danijela Ugrenović

Critic of The Morning Journal Predrag Miletić

Accordionist Dušan Stojanović

Organiser Nemanja Konstantinović

Stage Manager Đorđe Jovanović

Prompter Danica Stevanović

Assistant Stage Manager Sanja Mimica

The following folk songs are used in the performance: The Wine Song, Šiše rakije, Oj, čići opančići, Popevke sem slagal, Pogledaj me neverenice, Sećaš li se onog sata, as well as a dance Arapsko kokonješte.

Assistant Costume Designer Sara Bradić

Assistant Set Designer Sanja Bulat

Lighting Master Srđan Mićević

Make-Up Artist Dragoljub Jeremić

Stage Master Zoran Mirić

Sound Master Roko Mimica

Sets were made in the National Theatre’s workshops under supervision of Goran Milošević

Costumes and shoes were made in the National Theatre’s workshops

Male costumes’ designer Drena Drinić

Head of male costumes tailor shop Jela Bošković

Female costumes’ designer Radmila Marković

Head of female costumes tailor shop for Snežana Ignjatović

Shoe designer Milan Rakić

Head of shoemaker’s shop Žarko Lukić