The marriage and divorce of Figaro

Beaumarchais / Horvath / Mozart

Jelica Stevanovic

FIGARO ON THE STAGE OF THE NATIONAL THEATRE

The repertoire policy of the new National Theatre, founded in 1868, in the second half of the 19th century, due to the wars with Turkey, was passing through a period of stagnation, even regression. In the early eighties, to use the words of Milan Grol, “a circle of young actors, who, together with talent also brought some schooling and knowledge of foreign theatres, once against raised the repertoire ambitions”. So, Beaumarchais’s comedy came to the stage of the Royal Serbian National Theatre, the comedy which at one time, represented revolution in literature, thematically, formally, sociologically, ideologically...to be declared the instigator of the French Revolution – Le Mariage de Figaro. The premiere was on 29th March 1884. According to the facts left to us by Živojin Petrovic, the play was translated by Milovan Glišic and entitled The marriage of Figaro or a Crazy day, directed by Toša Jovanovic, and Davorin Jenko conducted the orchestra playing Mozart’s music. Count Almaviva, Governor Prefect in Andalusia was played by a favourite actor and talented singer Raja Pavlovic, his wife Countess Rosina was played by famous Vela Nigrinova, and Marija Cvetic was Suzanne, countess’s first maid and Figaro’s fiancé. Figaro, count’s valet and castle marshal, (cheerful, wise, skilful servant, direct heir of all servants-factotum from Siro to Harlequin and Mascarillo, depicting Beaumarchais to the greatest posible extent; he is, in fact, an autobiographical character and that is why he is more life-like, plastic, more convincing of all his predecessors) – was played by a leading actor and director Svetislav Dinulovic “who enchanted the audience with his irresistible and inexhaustible comic mastery improvisations. The rest of the characters were played by: Mileva Radulovic (Marcellina – housekeeper), Dimitrije Kolarovic (Antonio – gardener, Susanna’s uncle and Fanshetta’s father, Miss Maksimovic (Fanshetta –Antonio’s daughter), Miss Fransinel (Cherubino – first page to Count), Mr. Popovic ( Bartolo – doctor in Seville), Lazar Lugumerski ( Basilio– Countess’s piano teacher), Marko Stanišic ( Don Gusman Bridoazon – local judge), Mr.Božovic (court bailiff), Mihailo Risantijevic (Grin-soleil – young shepherd) and Miss Naumovic (young shepherdess). At that time in Belgrade, in its young theatre, very often the premiere was the only performance. The audience obviously liked The Marriage of Figaro because on 6 August there was the second showing, and on 7 February 1887, yet another one. Translated by Milan Grol, under the title The Marriage of Figaro or a Crazy Day the performance was staged with undisguised ambition: it was the first time that dr Branko Gavela (new director and Drama Director) was directing in Belgrade, Vladimir Žedrinski was set designer and costume designer, Jovan Srbulj a conductor, Alexander Fortunato at that time director of Ballet and choreographer, prepared the ballet dances in the fourth act, and two casts of characters were rehearsing. The premiere was on 12 May 1926. Unfortunately, playbill was not preserved, but the reviews show us that the following actors took part:Vitomir Bogic (Count), Desa Dugalic (Countess), Nikola Gošic (Figaro), Žanka Stokic (Suzanne), Ana Paranos (Marcelline), Dara Miloševic (Cherubino), Miss Dugalic (Fanshetta), and also Dimitrije Ginic, Milovan Milovanovic, Miodrag Ristic and Vlasta Antonovic (but it is hard to say in which roles). To use the words of a critic “The last night performance was a very pleasant evening for spectators, and for the theatre itself a guarantee for even better and more pleasant evenings”. Gavela, as was expected of him, for his debut on the stage of the National Theatre, chose a difficult task - Beaumarchais’s comedy, “light as a lace and as a lace full of bundles of love, jokes, stupidities, intrigues. Where every word is like a verse, every step like a charming dance. Where tiny wheels must not stop or miss a beat among the rubies of this glittering, for ever babbling, the most complicated watch ever to come out of the hand of the watchmaker, Beaumarchais”. And, as if that was no enough “Gavela, wanting to be both good director for spectators and good teacher for actors, had audacity to prepare two completely different casts, from Count Almaviva to the Second Shepherdess.” Cast at the premiere was worthy of the trust: Miss Dugalic “knows how to be excellent from the beginning to the end”, Žanka Stokic “unsurpassable incomparable in Suzanne’s mischiefs, and yet, not through her own fault maybe she was not a little Suzanne”. Ana Paranos “always truthful behind the grotesque mask”, Darinka Miloševic and Miss Dugalic “correct”, Bogic “lover above anything else”, and Mr. Ginic, Mr. Milovanovic, Mr. Ristic and Mr. Antonovic, contributed a great deal to the success”. For Nikola Gošic, in the title role, critics found but one epithet – good. Although the critic misses no opportunity to comment that in theatre as “a school of pure language and dignified movement” the language is not looked after properly, so you could hear incorrect expressions, he predicts nice fate of the performance: “The Marriage of Figaro seems to be a play which both theatrical gourmands and divided audience will watch with equal pleasure”. The playbill of the first re-run, played on 15 May, tells us that Vladeta Dragutinovic was Count, Nada Riznic Countess, Aleksandar Zlatkovic Figaro, Žanka Stokic Suzanne again. Teodora Arsenovic Marceline, Milan Ajvaz Antonio, Ružica Tekic Fanchetta, Miss Miloševic was Cherubino again, Milovanovic Bartolo, Dimitrije Ginic Basilio, Marko Marinkovic Don Cusman, Antonovic his secretary, Petrovic court trainee, Ilic young clerk, Velimir Boškovic Pedrillo, Nikolic young shepherd and Milica Bošnjakovic young shepherdess. Zlatkovic attracted more attention than his predecessor. Although of the opinion that this artist is at his best in contemporary drawing room comedies, critic states that as Figaro “he was alive, light, throwing words with ease and humour. He was servile and impertinent, which is a very successful illustration, significant at the same time, of the true character of Figaro.” the Count and the Countess in this second cast were not to the critics’ liking: “Dragutinovic, not a true nobleman, Mrs. Riznic, also, not a true aristocrat. Both coarse – Mr.Dragutinovic, in the second act, looked like Bersten’s Thief- without any refined pose or gesture, without that fine irony. And especially Mrs Riznic, without realising situation in a flash”. Ajvaz, Marinkovic and Miss Tekic were singled out from the remaining cast as being “truly successful” in their creations. Critics’ prediction that the performance will be a success with the audience proved to be true – Figaro was on the repertoire for four seasons, and during that time was played 16 times.

* * *

A play by Odon von Horvath Figaro is Getting Divorced has never been played in Serbia.

* * *

Mozart’s comic opera, based on the libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte, Le Nozze di Figaro has enviable continuity of presence on the stage of the National Theatre. The first staging of this opera was on 5 February 1936. Predrag Miloševic was the conductor, Josip Kulundžic director, Aleksandar Binicki translator, set designer Vladimir Žedrinski, costume designer Milica Babic, and Anatolij Žukovski prepared the ballet. All the stars of the opera took part: Rudolf Ertl (Count), Bahrija Nuri-Hodžic (Countess), Kornelija Ninkovic Grozano (Suzzanne), Milan Pihler (Figaro), Žarko Cvejic (Bartolo), Evgenija Pinterovic (Marcelline) and others.

Here is the list of subsequent premieres and revivals:

21 March 1946. translated by Stanislav Binicki. Conductor Predrag Miloševic. Branko Pomorišac revived it as a director. Set designer Vladimir Žedrinski. Costume designer Milica Babic.

7 April 1956. Translated by Stanislav Binicki. Conductor Oskar Danon. Director Sofija-Soja Jovanovic as a guest. Set designer Miomir Denic. Costume designer Milica Babic.

24 October 1964. (revival – based on Soja Jovanovic’s directing) Translated by Stanislav Binicki. Conductor Borislav Pašcan. Set designer Miomir Denic. Costume designer Milica Babic.

24 March 1970. Translated by Stanislav Binicki. Conductor Borislav Pašcan. Director Ani Radoševic. Set designer Miomir Denic. Costume designer Milica Babic.

26 March 1988. Translated and adapted by Mladen Jagušt. Conductor Mladen Jagušt. Director Viktorija Pižmoht. Set designer Milutin Ilic. Costume designer Ljiljana Orlic.

22 March 1997. . Translated and adapted by Mladen Jagušt. Conductor Jovan Šajnovic. Director Aleksandar Zlatovic. Costume designer Ljiljana Orlic

SLOBODAN UNKOVSKI, director

SLOBODAN UNKOVSKI, director

He was born in 1948 in Skopje. He graduated directing in 1971 from the Film, theatre and television Academy in Belgrade in Prof Vjekoslav Afric’s class. From 1971-1981 he was a director and drama manager of the Drama Theatre in Skopje, senior lecturer at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Skopje (1983-1987), as a holder of Fulbright grant he taught directing at the University of New York (1987/88), and at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA USA, he taught acting and directing (1988/89). During 1990 he was “Artist-in-Residence” in the American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, Ma USA, and in The National Theatre, Athens. From 1996-1998 he was Minister for Culture in the government of the Republic of Macedonia. Now he works as a professor of directing at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Skopje and he is in charge of post-graduate studies of directing. Slobodan Unkovski is one of the most significant directors of ex-Yugoslavia, and with playwright Goran Stefanovski ( whose ten plays he staged), he represented a tandem of authors who managed to express theatrical views of one whole generation of artists. Although the beginnings of his career coincided with the period of flourshing of so called director’s theatre (one of his first performances Nothing – based on Arthur Kopit’s text, was a radical experiment and it was pronounced best at Sarajevo’s MESS), Unkovski remains true to the dramatic text. In his plays all theatrical components are optimally expanded, (from set design and costume to sound, scenic movement, music, light design), and they are always in some sort of a perfect balance with the text and acting; any playwright can only wish that Unkovski would direct the first showing of his play (and the list of playwrights is impressive...from Goran Stefanovski, Milica Novkovic, Rudi Šelig, Dejan Dukovski... to Milena Markovic). But his craftmanship in directing is most clearly shown in coperation with actors; a whole array of unique actor’s creations was accomplished in Slobodan Unkovski’s performances. Unkovski a a world-known artist whose performances represent a turning point not only in the work of individual artists, but also in theatres he worked in. Critic Kevin Kelly in the Boston Globe as one such milestone called his direction of Brecht Caucasion Chalk Circle in American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, USA, the theatre where, among other important artist, Robert Wilson also directed. His Proud Flesh by Stefanovski for Drama Theatre, Skopje, Beautiful Vida by Šelig for Chamber Theatre 55, Sarajevo, Croatian Faust by Šnajder and Theatrical Illusions by Corneille for the Jugoslav Drama Theatre represent such dates in history Performances directed by Slobodan Unkovski took part in various European theatrical festivals: Croatian Faust by S.Šnajder at the Theatre of Nations in Nancy 1984, Powder Keg by D.Dukovski at the Bonn biennial 1996, Railway Tracks by Milena Markovic at Wiesbaden biennial 2004, He participated three times at Bitef (1975, 1980, 1991), at international theatre festivals in Caracas (Venezuela), Bogotá (Columbia), Chividale (Italy), London (great Britain), summer Festival in Hamburg, Dubrovnik Summer Festival, Split Summer Festival. At the Sterijino Pozorje Festival he was a guest 11 times and he won 5 Sterija Awards:

Jane Zadrogaz, G. Stefanovski, extraordinary Sterija Award for the best performance, 1975)

Proud flesh, G.Stefanovski, (Extraordinary Sterija Award for directing, 1980)

Croatian Faust, S.Šnajder (Sterija Award for directing, 1983)

Happy New 1949, G.Mihic (Sterija Award for directing, 1985)

Tower of Babylon G.Stefanovski ( Sterija Award for directing, 1990)

Some of the more important performances directed by S.Unkovski are:

Jane Zadrogaz, Drama theatre, Skopje

Proud Flesh by G.Stefavovski, Drama Theatre, Skopje

Tattooed Souls by G.Stefanovski, Little Brona Theatre, Moscow

Caucasian Chalk Circle by B. Brecht, American Repertory Theatre, Cambridge, USA

The Fourth Sister by Januš Glovacki, The National Theatre, Athens

The Winter Tale by W.Shakespeare, American Repertory Theatre, Cambridge, USA

Peer Gynt by H Ibsen, The Slovenian National Theatre, Ljubljana

Sarajevo by G.Stefanovski, international coproduction (Sweden, Belgium, Germany)

Theatrical Illusion by P.Corneille, JDP, Belgrade

Powder Keg by D.Dukovski, JDP Belgrade

The Misanthrope by J.B.P. Molliere, SNG Ljubljana

Oreste by Euripides, the National Theatre of the Northern Greece, Thessalonica, Epidaurus

ÖDÖN VON HORVATH

ÖDÖN VON HORVATH

(Sušak near Rijeka, 9 December 1901 – Paris 7 June 1938)

He is considered to be one of the most important playwrights of the German speaking population. Horvath’s father was Austrian-Hungarian diplomat, and his mother was Czech by origin. His family often moved from one place to another, from Belgrade and Budapest to Bratislava, Vienna, Munich. Besides his mother tongue, German, Horvath spoke Hungarian, Serbo-Croatian, Czech, Yiddish and French. He thought of himself as of a Middle European writer, and although he had Hungarian passport, he thought of the “term” fatherland” as foreign to him. His first writings were published in a satirical magazine Simplizissim, and he was almost expelled from school in Bratislava because of them. He interrupted schooling in 1922. After a stay in his parents’ house in Murnau, he left for Paris, and then in 1924 for Berlin were his writings met with approval of the intellectual circles. For a time he did some voluntary work for the German League for human rights, which made him more aware of the people on the margins and considerably influenced his future work. Many of his literary works were written in cafés where ordinary people gathered. The first play Cable Car from 1927 was based on a real life story – a strike which erupted after a worker got killed on the cable car in the Bavarian mountains. After the success of his second play At the beautiful appearance, Horvath would search for the themes for his plays among members of lower middle class, treating them satirically but not without affection. Formally speaking he continued to experiment with so called “folks play” (Volksstuck) genre in which he introduced elements from mass culture vocabulary. As Nazism was getting stronger he left Germany, and his plays, although popular, were taken off the repertoire of the German theatres in 1933. During his short life he wrote some short stories, a few novels (Eternal Petit Bourgeois, A child of our time, Youth without God) and plays (Stories from the Vienna forest, Don Huan Comes back from War, Cazimir and Caroline, Italian Night, At the beautiful Appearance, Faith, Love and Hope, Murder in Mord Street, Cable Car, Sleep, my little bride, Trivial Love Story, Serenade, Ela Valo Case. While some critics think of him as the greatest German dramatist after Brecht, or even better (Peter Handke: “Horvath is better than Brecht”), others have a certain reservation concerning artistic finishing, and “depth” of his works. Marcel Raich- Ranicki belongs to this second group. In his book Canon of German Literature he says: “Playful and a bit sloppy Horvath, imaginative bohemian, left a significant opus behind him. All his plays were written slovenly and in a hurry, yet he managed to create a few theatrical masterpieces, among others Stories from the Vienna Forest and Casimir and Caroline. Best suited term for his plays is volksstuck (folksplay), even though the author, using the means of the “folks play” and a dialect, questions so called populism and by using language of small people he exposes to criticism their milieu and their way of thinking. Sensitive outsider, Horvath focuses and unmasks a typical petit bourgeois of the beginning of the 20th century, the petit bourgeois who camouflages his usual speech with pretentious empty phrases of the learned jargon”. Horvath’s work was almost forgotten for two decades after his death, but when a younger generation of writers, in the sixties of the last century, started to explore the sources of Nazism in Germany, he was rediscovered and had a great influence on the work of Friedrich Durrenmatt, Franz Xaver Kreatc, Botho Strauss and others.

PTERRE-AUGUSTIN CARONE DE BEAUMARCHAIS

PTERRE-AUGUSTIN CARONE DE BEAUMARCHAIS

Pierre Augustine Carone de Beaumarchais is an extremely complex, versatile, many talented person whose life path was quite atypical for the century he lived in, the 18th century. He was born in 1732 in Paris, centre of the European culture, spirit, splendour, intrigue...He comes from a modest background, but at the age of 21 he succeeded in constructing a new regulator for pocket watches. Thanks to that invention and perhaps more to the unexpected, brave and brilliantly led and won law-suit against then famous watch maker who tried to steal the invention, and an extraordinary ability for self promotion – young Beaumarchais made to the court and the title “court watch maker”. Once he managed to reach the “high society”, there was no stopping this capable, ambitious young low class man, upstart. In the course of several decades he became one of the richest man in France, and one of the most famous man in Europe, influential politician, great merchant and entrepreneur, secret agent to Louis XV and Louis XVI, military leader, inventor (beside pocket watch, he perfected the pedals on the harp, and he also left behind a great number of projects in different fields: legislation, commerce, technology of manufacturing peat into coal, agriculture...), well-known litigator (starting with the already mentioned law suit in 1733 until his death in 1799, he continuously led numerous and varied litigations, sometimes more at the same time and the one against the Comedie Française lasted fifteen years), ladies’ favourite and of the whole court, confidante of many important people of the century, musician, composer...and author of the comedies of which two are considered to be world classic –Le Barbier de Seville and Le mariage de Figaro. Chronicler Hardy says that Beaumarchas “was one of those great forces which Maker, from time to time, brings to this world, to the great astonishment of his contemporaries, and to the glory of their century”, while one of the wittiest people of that time, Voltaire, admits: “ I read all Memoirs by Beaumarchais: I have never had such fun...Strange man! He has it all, joke, reality, joyness, strength, touching, all kinds of eloquence, and yet he searches for none, and defeats all his opponents, and teaches his judges a lesson”. In that, 18th century, especially in France, spirit and wit are the most appreciated qualities. “The eighteenth century not only created that spirit but it was the only one that could do it: the century in which all conditions for its creation were fulfilled.” That spirit was responsible for Beaumarchais’s strange path of life, and he himself said: “I don’t know the century in which I would rather live” – aware, in all probability that only then and there his luxuriant spirit could take him so far and ensure him a life richer than ten average ones.

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART, (1756 – 1791)

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART, (1756 – 1791)

He was born in Salzburg, one of the musical centres of the 18th century Europe, in the musical family of the German origin. His Father Leopold was a composer and a violinist who early discovered and supported the exceptional talent of his children. His daughter Maria Ana played the piano excellently at the age of nine, and his son Wolfgang at the age of five. Starting in 1761, they often gave concerts, and the next year they began touring in Austria and other European countries. The first recorded and saved composition by young Mozart is from 1762. The very next year they went to Paris, where they spent three weeks at Palace of Versailles, and Mozart performed for Maria-Antoinette. From 1768 they enjoyed the hospitality of the Viennese court. The year after that at the court of the patron Count von Mesmer, his first singspiel Bastien and Bastienna was performed and soon after that his first opera buffo La finta Semplice. From 1769 till 1771 still a boy and already immensely popular throughout Europe, Mozart spent sixteen months in Italy where he perfected his knowledge and received great and rare tributes and honours, as the order of the “golden spur” with a title of a chevalier (Gluck was the only musician who received this honour before Mozart). In the next two years Mozart came to Italy on two occasions, but he remained in contact with the leading high baroque and rococo Italian musicians. At the age of 21 he spent an extended period of time in Germany where he met composers who were trying to introduce German spirit into the opera. Thus he had the opportunity to get to know contemporary opera of Italy, France and Germany, and he wrote to his father in 1778: “the will to compose became a fixation with me: rather French than German operas, but Italian rather than French or German”. The last ten years of his short life he spent in Vienna, as, what we would call nowadays free-lance, as one of the first in the history of the mankind. That means that, thanks to his short temper, as well as a rebellious spirit which was, no doubt, influenced by the French revolution, he had no patron and was forced to make his living by giving concerts, selling compositions and giving lessons. He died in poverty. He composed with incredible easy and speed. That is how he managed to compose, during his 35 years of life, 54 symphonies, 30 concertos, 3 concert symphonies, tens of pieces of chamber music, vocal music and music for solo piano, 18 masses, one oratorio, three singspiels, ten operas, all in all 622 finished and 132 unfinished compositions.

LORENZO DA PONTE

LORENZO DA PONTE

Lorenzo Da Ponte ( real name Emanuele Conegliano) was born in Italy in 1749 and died in New York in 1838. Like Beaumarchais and Mozart he also had a very unusual and rich life. He came from a Jewish background, but in his youth he converted to Christianity and even became a Catholic priest. He taught rethorics for two years at the Catholic seminary in Treviso, where he got fired because of his attacks on the high society. When he was 34, emperor Joseph II appointed him a librettist to the Italian Opera in Vienna. There he would meet Mozart and their colaboration would last till the death of Joseph II, but in those few years Da Ponte wrote librettos for three Mozart’s operas which are now considered to be classics: Le Nozze de Figaro (1786), Don Giovanni (1787), and Cosi fan Tutte (1790). After that, till 1805 he travelled around Europe changing professions: book seller, Italian language teacher, librettist...and finally he left for the USA where he engaged in the book selling business and organisation of the first opera companies. He wrote about 60 opera librettos, and also adaptations of other librettos, as well as memoirs and dramas.

Slavko Milanovic

FIGARO IN THE THEATRICAL TIME

In Slobodan Unkovski’s performance Beaumarchais’s and Horvat’s Figaro are not performed in chronological order as was done many times before (for instance, in Belgrade some twenty years ago, with Paolo Madjelias a director). It would be expected that Beaumarchais’s Le Mariage de Figaro first performed in 1784 precedes the play by Odon von Horvath in which the story continues, as the writer says, “a few years after Beaumarchais’s wedding”. This would be logical, all the more so, as Horvath adds that due to the “timeless character of the theme” the action in his play takes place in the thirties of the 20th century. In Slobodan Unkovski’s performance the action of both plays happen simultaneously. At the same time when Horvath’s characters cross the border fleeing from revolution, the plot of Beaumarchais comedy which precedes that revolution, starts to unfold. Why was this seemingly formal intervention necessary? Especially if testing the power of spectator’s perception is nothing new – post modern and post drama theatre conducted the experiments of that kind numerous times, and theoretician of “deconstruction of spectator’s attention” Hans Tis Leman explained the necessity for this. According to the post drama theory the traditional wholeness of a story is only a “theoretical fiction”, which corresponds neither with the theatrical practice nor experience of the contemporary spectator; contemporary theatre cannot be at the service of adding “logical (that is dramatic) order into the confusing chaos and fullness of being”. All that is well known to the modern spectator even without drama and theatrical theories (which, after all, always come after artistic practice). But if we dare to look for theoretical validity of the Unkovski’s procedure, we would find it in the Mikhail Bakhtin’s chronotope theory. According to this theory, whose aim is to try to explain in what way individual life experience compresses into artificial art form, which in the end has to give impression of the reality itself, the thing is in author’s intervention on spectator’s perception of time and space. Chronotone (timespace- mathematical term from Einstein’s theory of relativity) allows time not to unfold mechanically, in chronological order, but in it “sequences of time and space are being mixed and crossed, measured one by the other”. Just like the scenes from Beaumarchais’s, Mozart’s and Horvath’s Figaro cross, portray and “measure one another”. There is a stronghold for Slobodan Unkovski’s concept and the idea that were inhereted from the time when those works were created. Before becoming a symbol, Beaumarchais’s Figaro had already been some sort of a revolutionary instrument, protagonist of the 18th century idea of progress which leads to freedom and equality, written in the Declaration of human rights. Horvath’s generation experienced the defeat of the ideas from the Beaumarchais epoch. In a short introduction to his play he wrote: “In Le Mariage de Figaro the forthcoming revolution is announced thunderously” and added that in his play Figaro is Getting Divorced “probably nothing will be thunderously announced”. Horvath seems to anticipate the idea of the end of history, which was based on the idea of progress. He does not believe, as Beaumarchais does, in emancipation which will make Figaro a free citizen in whom the great sense of Universal History will be embodied. It can sooner be said that he is resigned over the possibility that “there is nothing beyond the idiotic course of events”. And he admits that his only hope is that a storm will not switch off “the faint light of humanity. Every work from the drama history is covered with layers of critical comments and interpretations left behind by time. And when you uncover all those layers and come to the work itself, a problem of inner contradictions that it contains arises. Slobodan Unkovski talked about that problem on the occasion of Shakespeare’s Winter Tale which he directed in the American repertoire theatre in Cambridge (USA). Based on the note by dramatist Gideon Lester, Unkovski noticed that “in all probability Shakespeare wanted to write the Winter Tale as a pastoral play, but the writing took him in a direction of tragedy”. With Beaumarchais Figaro the thing is even more complicated: the writer himself did his best to make the play the fiercest possible pamphlet against the ruling hierarchy. (Jean Devigno says ironically that Figaro is a drawing room comedy so that Beaumaarchais could place his “tirades”). As if Beaumarchais wanted to confirm L.S.Mercier’ theory from 1773 that “theatre is the strongest and fastest means to arm the forces of reason and to throw large quantities of light into people”. His Figaro became a politician, representative of the so called third class, destroyer of absolutism and nobilities’ privileges, rebel against limitation of personal freedom and freedom of thought. He and count Almaviva were no longer seen as those infinitely funny characters from The Barber of Seville around whom – as Beaumarchais himself wrote at one time, “life flows and splashes so hilariously, so happily, so joyfully,”, and only Mozart was able to see them as such in his Le Nozze de Figaro. Horvath knew the consequences of various attempts to “throw light into people”. Only five years after the premiere of Figaro censorship was banned, and instead of that many actors and directors had to prove their loyalty to the Revolution on daily basis or they would end up on the guillotine. Today we know that Figaro had an alternative – if Beaumarchais only let him (as in some Pirandello twist) stay what he had always been – a theatrical character, instead of being a symbol of revolution. Controversy on whether he as an orphan was equal to count Almaviva to whom sky itself allocated privileges. In reality Figaro could not win. His “noble background” could only be established in theatre. Because in theatre his genealogical tree is older and more diversified that Almaviva’s. As Bogdan Popovic says smartly in his study on Beaumarchais: “Count Almaviva’s origin does not go further back in the past then Crusade Wars, while Figaro’s, going back through the Middle Ages, has its roots in ancient times”. “Stand next to Figaro”, says he, “and look over his head in the distance, you will see a procession of original personalities of all nations, all times, all members of one family. Through Moliere, Moretto, far at the end Plaut and Terentius, to Aristophanes – you will see his forefathers Epidicus, Dave, Goethe, Parmenon, Sir, Styrax... Procession is enormous; Figaro’s roots are in the ancient beginning of theatre and comedy as a genre”. If, as advised by Bogdan Popovic, we again stand next to Figaro, and look, not over his shoulder, but into the future, we will see that he is faced with the same old dilemma: reality or theatre. Horvath’s play is also covered with layers of interpretations which tended to pull away his Figaro – from the theatre into reality. According to Theodore Zuckor Horvath’s Figaro failed Beaumarchais’s, because in contrast to his archetype he became petty bourgeois reactionary. Once again critics tried to see a real person in Figaro, protagonist of history, they praised his rejection of petty bourgeois xenophobia, his anticipation of the coming Nazism and his escape to internal emigration. We do not know who the theatrical offspring of such a Figaro are, because we do not know in which direction Horvath’s conception of folk play (volksstuck) would develop. Maybe he would return from the world, the great world of history and ideology, into theatre as Becket’s clown, or his predecessor Harlequin, who solved all great questions concerning rights of man with gags. At the quizzical question of his “count Almaviva”: “Harlequin, How many fathers have you got?” he would answer: “Only one, signore, I am a poor man, we paupers only have one”. Unkovski never said that he was interested in the problem of discontinuity of history, or defeat of humanity, or formal testing of the problem time/space. Unkovski did not say that, and he would not say that even were he asked directly. The only thing he would eventually claim in connection with his concept is – that there was no concept. Unkovski does not implement his concept onto actors and other associates; he develops it together with them. Yet I believe that he would not deny that he leans towards Figaro who belongs to the world of theatre. Because in that world The Great History allows man to satisfy his need to “ pack, even the greatest ruptures, into the limits of his life”, as once Unkovski said, in an occasion unrelated to theatre In that world there exist, at the same time, next to one another, Mozart’s, Beaumarchais’s, Horvath’s Figaro, Suzanna, Count Almaviva, Countess, Bartolo. That is the world where time is not historic but, as in Einstein’s dreams by physicist and writer Alan Lightman, time can go backwards, to stand in eternal current time, to be a feature, to be measured by distance from the centre of the Earth, in it past can change if need be, it can be a local event, it can stop, events from different epochs can flow next to each other, as time flows.

Jelica Stevanovic

FROM COMEDY TO OPERA

Da Ponte had to trim the thorny woods of the Le Mariage de Figaro, until he managed to collect a handful of flowers that he could pick; and Mozart managed to interweave, permeate and illuminate that skillfully made libretto by Da Ponte with cristal melodies, filled it with virtuous feelings as pure as the clear mountain water, - and with his golden humour.

Bogdan Popovic (1925)

Eruptive temperament, intelligence, luxuriant talent, wit, sense of comic and satiric, extraordinary power of observation, freedom-loving-rebellious spirit are the things that connect Mozart to Beaumarchais. It is no coincidence that the union of those two great artists, with the help of Da Ponte, produced one of the best and most performed operas in the world. During his last “Viennese” period, Mozart met Italian composers, but also German ones – Haydn, Gluck and others. A matter of the utmost importance for the creation of Le Nozze di Figaro, along with the tradition of opera buffo and opera serie, were also Gluck’s opera reform, spirit of the French Revolution and meeting Italian librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte. A fact that arrangements with Da Ponte and the work on the libretto started in 1783 and opera was finished at the end of April 1786 shows us how difficult the task was and the seriousness with which they approached it – to create an opera based on drama (especially work like Beaumarchais’s Le mariage de Figaro. “The best thing is when a good composer, the one who understands theatre and who is able to contribute to the work, meets, as a real phoenix, a clever poet...” said Mozart about the role of a composer in writing a libretto. In order to adapt the complicated structure of Beaumarchais’s comedy to the needs of opera genre, Da Ponte took only the basic, the love plot. Satire is numbed, reduced to a minimum, the number of characters reduced. And yet, libretto was not turned into a stereotype story in which youth and love conquer old age and lust, as often was the case in contemporary Italian operas. The story kept a lot of Beaumarchais’s spirit, it is life-like, plausible, some satirical paragraphs were kept, especially those in Figaro’s arias, superiority of common people over nobility can be clearly seen. “Mozart shows an unusually strong gift of observation of the psychological characteristics of his characters, and he far surpasses all of his Italian paragons. All characters, no matter how different, speak by means of Mozart’s music in a language that we immediately recognize. Mozart does not use “leitmotifs”, again and again he uses new tones to emphasize all feeling and all passions, yet remaining always true and honest. He finds a right expression for everything and also the right measure: for pride and humiliation, daring and cowardness, for pain and insults, for rage and resistance, love and mischievous wooing, for hating life and death”, noted Joseph Andreis. It is said that, being aware of all the possible problems comedy Le Nozze di Figaro might have had if performed and that it was still banned in some European countries, Da Ponte resorted to craftiness and came to the Emperor praising Mozart, evading mentioning Beaumarchais, and so he got the permission to show the opera. The premiere was on 1 May 1786 at Burgtheater in Vienna with Mozart as a conductor and it was a great success. In December that same year in Paris the opera triumphed. Then comes a series of successes throughout whole Europe, as well as South and North America.

Jelica Stevanovic

SERVANT WINS THE WAR

More about Beaumarchais’s Mariage

In writing dramas Beaumarchais was an innovator, because he was an enemy of tradition in everything he did in life. The furthest he went in this struggle of his was probably in Le Mariage de Figaro. Le Mariage de Figaro or a crazy day (in some translations Crazy banquet) is the second part of Beaumarchais’s drama trilogy which comprises of the Barber of Seville and Mother the Adulteress or The Second Tartuffe. The basic plot and the characters of the first story were taken over from the comedy heritage whose roots are in comedy del’arte (and even earlier, in Plautus and Terence) and which were gladly used by French authors of the 17th and 18th century. An old tutor stands in a way of a young couple in love, but with the help of a lucid and loyal servant young lover manages to outwit the old man. Those are the heirs of Pantaleone, Columbina, Harlequin and other well known drama models. However, the main character of all three comedies – merry, wise, brisk servant Figaro, besides being a direct heir of all servants-factotum from Siro, through Harlequin to Mascarillo, is, in fact an autobiographical character as he, to the greatest possible extent, depicts the author himself; And that is why he is more life-like, more plastic, more convincing than all of his predecessors. The character of the main hero is portrayed with great precision, but other characters, at least in Le Mariage de Figaro, do not fall far behind. The basic plot is crossed, followed and enriched by numerous secondary plots, also interesting, funny, fast, realistic. Beaumarchais introduces prose dialogue into comedy, short, wise, yet simple sentences, many of which became later a part of everyday speech, almost like proverbs. The mentioned novelties in form are present in the first part of trilogy, in Le Barbiere de Seville, which is all about laughter, pure, simple, healthy laughter, wit and fun. However, Beaumarchais introduces into Le Mariage de Figaro certainly the bravest and in socio-historical sense the most significant innovation – he openly turns against the ruling class, against existing system, against gentry, even against emperor himself. Although he did everything possible to come closer to the highest circles, or even the court, Beaumarchais is aware of excessive luxury of the French gentry in the 18th century, and the price of that luxury. His exquisite sense for noticing details reveals every corruption, misuse, distorted meaning and justice, every evil and injustice, as well as fundamental weakness and impotence of a dying class and system. And in spite of numerous picturesque love plots and naive intrigues which are in the foreground of Le Mariage de Figaro, the whole play is, in fact, a battle between common people and gentry, i.e. Figaro and Count, in which all skirmishes as well as the whole war wins – the servant.

Mirjana Miocinovic

THEATRE AND GUILLOTINE

When Jean Pierre Lenoir, Prefect of the Paris police, received Beaumarchais’s comedy for approval he was not sure whether that play, although full of allusions to not such a small number of current problems (power of the police, freedom of speech, and privileges of the aristocracy) could be thought of as subversive. As he was not able to do his job of an approved censor without wavering, he sent the play to Louis XVI himself. In her memoirs, Madame Champagne, who read the play to the king, recorded his reaction: “this is abominable, this will never be performed; Bastille should be pulled down so that this play would have no dangerous consequences. This man attacts everything in this country that is worthy of respect”. Whether King’s disapproval was so finely formulated, whether it was all vero, we do not know, but without any doubt it was ben trovato. This sentence is quoted in every work about Beaumarchais, in favour of clairvoyance, both writer’s and King’s. The first Beaumarchais’s reaction was: “King forbids performing Le Mariage de Figaro therefore it will be performed”. And so preparations for the premiere were under way in the official royal theatre – Comédie Française, the date for the premiere was set for 13 July 1783. Half an hour before the curtain was lifted, when it was impossible to come anywhere near the theatre because of the number of spectators, actors received the message warning them that, in case they went on with the play, they “would have the opportunity to see all the consequences of His Majesty’s wrath”. We would never know what those consequences might have been, as the actors cancelled the performance. But we know of the spectators’ wrath: they literary seized the theatre, stayed in it till dawn, and the already mentioned Madame Champaigne wrote, not without exaggeration that words “oppression” and “tyranny” had never been uttered with more bitterness. Monarchistic scripts of ruling are obviously of the kind that is naive enough as to not be able to foresee everything or at least they anticipated wrongly. Because, starting from that moment, Beaumarchais triumphs, noblemen arrange séances of reading his play, ladies faint in crowded drawing rooms, the writer himself breaks windows to let the air in, and one funny aristocrat, who feels like joking, says that Mr Pierre Ogisten “has broken glass twice”. And what else is there for the King to do then to approve the performance in a crazy, but the only remaining idea that the play might fail. The triumph started on 27 April 1784 with the first spoken line and lasted for the next seventy five consecutive nights. Not a single line was erased; the play became untouchable, but not the same thing could be said of its author; man is more vulnerable: Journal de Paris published a series of attacks on Beaumarchais private life, questioning his reputation, and one incautious writer’s reply printed in the moment when he lost his patience, cost him a prison, but not in Bastille, as could have been expected, but a prison for young offenders. Because who would look after opponents’ dignity. Even kings played on the card of humiliating one’s dignity, kings, who hold that same dignity so dear. As he made him look silly, depriving him of the martyr’s aureole, king released him from prison a few days later. More or less things were even with the two of them, with one added generosity on the king’s part: he approved the staging of Le Mariage de Figaro in Versailles; Maria-Antoinette, the queen proverbially ignorant of the needs of the common people, played one of the roles. As far as Beaumarchais was concerned he donated the profits to the poor. Eager for peace and quiet, rich enough to make it possible, he started building an imposing house in Saint-Antoine, close to the poorest part of Paris, some two hundred meters away from Bastille. In a half-finished palace he spent a turbulent night on 14 July 1789 and witnessed conquering of the dungeon. Some of his biographers credited him with almost a mythical role: according to them he was in command of pulling down the prison and levelling the ground where it stood. Was he able to resist the temptation in these moments and without any feeling of vanity remember king’s words predicting the important role his comedy would play in the history of that edifice and in the history of the world?

Theatre and Guillotine

Le Mariage de Figaro is the first Aristophanes comedy after Aristophanes(...), and so, in my opinion Le Mariage de Figaro became an historical event, it was one of the most significant political writings in the century of Montesquieu, Voltaire and Rousseau, a political piece that no political history of the French Revolution failed to mention as one of the most direct incentive for the last overthrow, in which, as in some kind of cataclysm, tragically, the complete centuries-old order perished.

Bogdan Popovic (1925)

Premiere performance

Premiere, November 16, 2008 / Main Stage

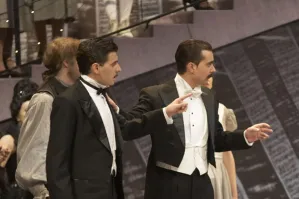

Director Slobodan Unkovski

Set designer Miodrag Tabački

Costume designer Angelina Atlagić

Composer Irena Popović

Choreographer Dimitris Sotiriu

Dramaturgs Slavko Milanović and Maja Pelević

Voice coach dr Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Assistant director Dragana Miloševski

Assistant director - volunteer Ana Konstantinović

Producer Borislav Balać

Premiere cast:

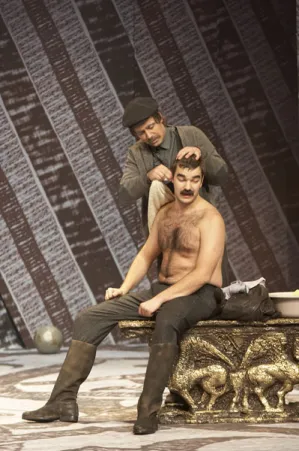

The Marriage of Figaro or a Crazy Day (Pierre Augustin Caron De Beaumarchais)

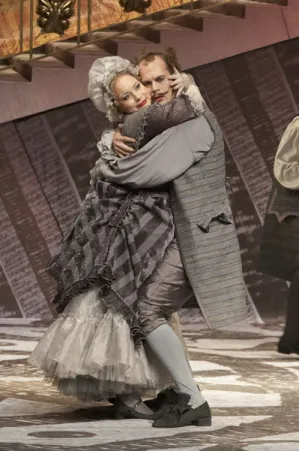

Count Almaviva Boris Komnenić

Countess, his wife Dušanka Stojanović Glid

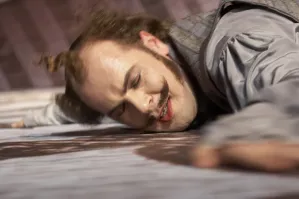

Figaro Miloš Đorđević

Suzanne, his fiancee/wife Nada Šargin

Marcellina Bojana Bambić

Bartolo Pavle Jerinić*

Cherubino Rade Ćosić

Fanshetta Iskra Brajović**

Premiere cast:

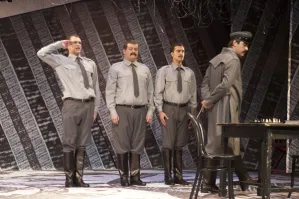

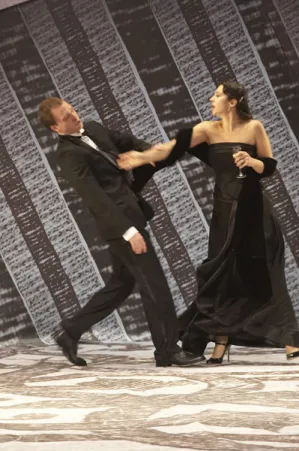

Figaro is Getting Divorced (Odon Von Horvath)

Count Almaviva Vojislav Brajović

Countess, his wife Olga Odanović

Figaro Igor Đorđević

Suzanne, his wife-fiancee Nataša Ninković

First frontierman/forester's assistant/sentry sergeant/cafe guest Bojan Krivokapić*

Second frontierman/Jeweler's assistant/Teacher/Antonio Stefan Buzurović

Third frontierman/Jeweler/Basilio/Sentry/Cherubino Stefan Bundalo**

Officer /Aldabert/Pedrillo Milan Vučković*

Josepha Teodora Živanović*

Maid/ Secretary /Fanchetta Dragana Milošević*

Midwife Jelena Vrcibradi

Mrs.Doctor Hana Selimović**

Older Child Andrija Gojković / Predrag Vasić

Younger child Predrag Vasić / Aleksandar Mladenović

* Fourth year student of acting in prof. Biljana Masic's class at FDU

**Fourth year student of acting in prof. Nebojsa Dugalic's class and expert consultant Borisav Grigorovic at BK Academy

Premiere cast:

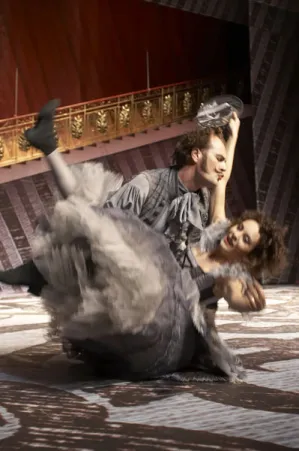

Le Nozze di Figaro (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart)

Count Almaviva Predrag Milanović

Countess, his wife Sofija Pižurica

Figaro Vladimir Andrić

Suzanna, his fiancee / wife Dubravka Arsić

Cherubino Sofija Pižurica

Piano Tatjana Ščerbak Pređa

Clarinet (bass clarinet) Stojan Krkuleski

Flute Marija Milosavljević

Violin Miljana Popović

Cello Ana Ristić

Percussion Miloš Vasić

Organizer Nemanja Konstatinović

Stage manager SašaTanasković

Prompter Gordana Perovski

Rehearser Tatjana Ščerbak Pređa

Assistants to costume designer Snežana Pešić Rajić and Olga Mrđenović

Lighting designer Miodrag Milivojević

Mask-making artist Dragoljub Jeremić

Technical director Zoran Mirić

Sound designer Perica Ćurković

Costumes were made in the workshops ofthe National Theatre and in the workshops of Nicola's sets were made in the workshops of the National Theatre.