The bacchae

tragedy by Euripides

A WORD FROM DIRECTOR

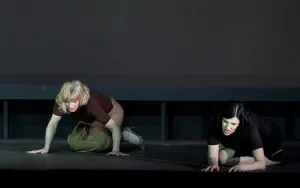

Talking about common opinion that Greek drama is something boring and static, the director is representative of future audience during rehearsals and I don’t accept to be bored while I work. The “Bacchae” have that Shakespearean moment – there is no tragedy without a comedy. Comical and funny parts exist only to make the tragedy even more severe at the end. I don’t expect the modern audience anywhere, be it in Stockholm, Berlin or Belgrade, to know the whole Greek mythology, therefore the play is based neither on mythical nor on historic point of view. During rehearsals we talked about the 60’s, about how everything was great – there was free love, sex, Woodstock, flower power, music, everything that was out of ordinary, very strict society. But then, only a few years later, there was a war in Vietnam, murder of Sharon Tate Polanski and events in Manson’s house. The thing that started as mild, pleasurable and loving turned into brutality.

Staffan Valdemar Holm

EURIPIDES

EURIPIDES

Euripides was born on the island of Salamis, near Athens, most probably in 485 BC. He was a well-educated man at the time and many chronicles indicate that he was in possession of a personal library. Ninety-two tragedies, out of which only nineteen have survived, and a satyr play have been attributed to his name. He won only four times in his lifetime at Dionysian theatre festivities, which were held every spring and once posthumously (for a group of plays including The Bacchae and Iphigenia in Aulis). Out of the three great tragedy playwrights, Euripides was the least appreciated during his life. If we take into account that Sophocles won twenty-four times and Aeschylus, even posthumously, according to different sources, fifteen times, it is clear that Euripides could not be considered successful at the time. However, out of all contenders, Euripides was selected one of the three winners of the year for twenty times. One can conclude that Euripides was not liked by the Athenians, not only because of the number of winnings, but also from Aristophanes satirical comments, which could be the reason why the elderly poet left his homeland in 408 BC, only two years prior to his death. He died in 406 BC on the court of Macedonian king Archelaus. The reason why Euripides was not appreciated as much as Aeschylus and Sophocles lies, among other things, in the new character of his work. In Euripides’s plays, the plot is run by the unsolicited and often vicious gods’ actions and not by the brutal but benevolent gods, nor by the hero’s free decision. Euripides did not think mythically any more. Although he was quite the connoisseur of mythology (Jan Kott speaks with sympathy about his “showing off with the expertise” in The Bacchae), Euripides has shown a rational attitude to religious beliefs, classical legends and myths that were an imperative for Greek classical drama. He dared to portray the gods as irrational, uncontrollable and devoid of “divine justice”. While Aeschylus, veteran of the Battle of Marathon, believed the war represents an opportunity to be heroic, Euripides found the war only an irrational act bringing forth physical devastation and suffer to the conquered. Because of his sophist scepticism, he could not accept “larger than life” characters that were depicted by Aeschylus and Sophocles with such credibility. Euripides is considered the first realist; his characters resembled real-life people whose fortunate or tragic destinies, irrational and immoral acts are not being reconciled with destiny in ethical discovery of high values, instead there is an absurd torment, which is being looked upon with indifference by the gods. Moreover, there was a veneration for his realism and skilful psychological insight when character portraying is concerned (especially the female characters), but Euripides’ lack of formal structure of tragedy was held against him (the prologue explaining previous events and resolution by God’s appearance on the stage “deus ex machina”). This is the prevailing reason why Aristotle, although he mentioned Euripides as a “poet of the most tragic events”, found Sophocles’ plays better than Euripides’ and considered them a model of tragedy. Classical philologists of XIX century (including F. Nietzsche) blamed Euripides not only for the formal imperfections, but also for the death of classic tragedy. Goethe, provoked by the ranking of the three great tragic playwrights, asks “Did any nation produce a playwright who could be worthy of untying his shoes? (…) If a modern man wants to speak ill of such a virtuous old poet, than manners require this should be done on knees.”

STAFFAN VALDEMAR HOLM

STAFFAN VALDEMAR HOLM

Born in 1958 in Tomelilla in Southern Sweden. Married to Bente Lykke Møller his steady set and costume designer. Studies in literature, theatre, film and art at the University of Lund. Studied theatre direction 1984-88 at the Danish Theatre Academy in Copenhagen. During this period a guest observer at Schaubühne, Berlin, following the work of Peter Stein. Founded Nya Skandinaviska Försoksteatern (New Scandinavian Experimental Theatre) 1989 after the example of Strindberg 100 years earlier. Started as a playwright- has written 7 plays and the most recent ”Vögelein” is playing at the National Theatre in Belgrade. Since leaving the academy he has directed around 60 productions, drama as well as opera mostly in Stockholm, Copenhagen and Malmö, but also in Berlin (Deutsches Theater), Vienna, Santiago de Chile and Madrid. His productions have been invited to different theatres and festivals, among others: to Schaubühne, Berlin and the Schiller Festival in Mannheim (Germany), BAM New York, Belgrade, to Madrid, St. Petersburg, Turin, Porto, Bergen, Sarajevo. 1990-92 steady engaged director at the Royal Theatre (Kongelige Teater) in Copenhagen. 1992-98 artistic and managing director of Malmö Dramatiska Teater ( the city theatre). 2002-08 artistic and managing director of Dramaten in Stockholm. Founder of ”Ingmar Bergman International Theatre Festival” in Stockholm and its first artistic director opening the festival 2009. Vice president of U.T.E. 2007-08 till Dramaten left the organisation. One of the initiative takers for the new European theatre network, Mitos21 which includes, among others: National Theatre London, Deutsches Theater Berlin, Tuneel Group and Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus, were hi is going to be artistic director starting february 2011. Has received several awards in different countries.

ТHE TRAGIC GAIETY OF THE BACCHAE

“None of the existing Greek tragedies is so saturated with religious images,” as is The Bacchae by Euripides, says Jan Kott in his most comprehensive study: Eating of the Gods, The Bacchae by Euripides. Kott says this play “shows off” Euripides’ erudition, and demonstrates once again, that he is among the most scholarly Hellene of his time. Besides the basic myth of Dionysus’ birth –child of Zeus and Cadmus’ daughter, Semele, and thus directly linked with the tragedy’s plot – Euripides, according to Kott, alluded to numerous other versions of the myth, and even questioned historical data on how the Dionysian cult arrived in Greece. And since, according to Plutarch, Dionysus is a god who is, “subject to constant changes of his beings” (thus the impressive list of his different names), things get even more complicated. Director Staffan Valdemar Holm frees the text of most mythological material. This is understandable as modern audiences do not necessarily come to the theatre conversant in the complicated mythological material essential to this play. The director’s decision is supported by the myth itself; not only because its countless variations show surprising similarities, but also because of Dionysus’ “kinship” with humankind today. As Euripides says Dionysius is “men’s best liked and the most fearsome god” because of his very human nature.” As Jan Kott states: “The Dionysus myth is at the same time genetic and cosmic… The myth speaks of man’s dual nature.” Human beings were created from Titan’s ashes. But the Titans ate Dionysus, before they were turned into ashes. The soul captured inside the body is a Dionysian substance that has survived in men.” As Tiresias says in the Bacchae, “much of this God has come into men.” We can also see it today. The 1960’s showed “the dearest” side of the Dionysian human nature. Like in some prolonged Dionysian festivities (which lasted for six days in ancient Greece), the world danced and sang for a decade, led by the “flower children” as modern “Bacchants.” In other, fearsome modern incarnations, Dionysus showed his face in the consequences of the Vietnam War or the horrific Charles Manson’s murders. Walter Kaufman in his study Tragedy and Philosophy says “an inexorable uniformity of both adversaries, Pentheus and Dionysus, contribute to the tragedy. The poetic force of The Bacchae carries a symbolic strength of an unbelievable conclusion: the rational fear of passion becomes lecherous; and a man blind for a vast beauty of irrational experience is destroyed by those who, giving up the reason, enjoy the blindness of their frenzy.” This inner battle is even stronger in a modern man, believes Carl Gustav Jung when he talks about “the Apollonian and the Dionysian” as distinct psychological categories: “Hindered instincts in a civilized man are tremendously devastating and more dangerous than the instincts of a primitive man who, to a certain degree, gives incessant vent to his negative instincts. The Bacchae could be considered a classic illustration of this phenomenon. Agave and the other Bacchae who dismember her son, Pentheus, are not barbarians but hyper-civilized mockers of faith who Dionysus punishes by making their frenzied rituals ultimately beastly. Director Holm consistently reminded actors in rehearsals that for the first two-thirds of the play The Bacchae is a comedy, and in the last part a brutal tragedy (such a tragedy that Aristotle declared Euripides “the poet of what is mostly tragic”). The rationale for such an understanding lies in Euripides’ technique. “The amusing parts exist precisely to make the tragedy even more poignant and horrifying,” Holm says. There is no paradox in Holm’s statement. Other playwrights of tragedies also used dramatic irony, comic interludes and dialogues to make this point. And, in several cases, Aeschylus’, Sophocles’ and Euripides’ tragedies do not end wretchedly. When Hellenic culture was at its peak and was, as Miloš Đurić puts it, “the most beautiful flower,” tragedy represented the affirmation of the “will to life”. Nietzsche speaks of cheerful, even joyful tragedy, which merely points to a complex idea of catharsis. In two-thirds of his masterpiece, The Bacchae, Euripides seems to return to tragedy’s very roots – a satyr play performed at the Dionysian festivities that did not have its later tragic seriousness. After all, music and theatre, without which the Dionysian mysteries would not have existed, are mentioned in The Bacchae several times. The theatre is the main topic and the main character of this play. The theatre reduced to its basic elements – acting and poetry. Bente Lykke Møller brought a minimalist scale model and costume sketches to the first rehearsal: the set design consisting of a wall, a bench and a black ball hanging in the air; costumes - modern clothes, harkening back to styles of the 1960s. Moller wittily commented on her minimalist designs: “The set and costumes should be boring; it is the actors who should bring what is exciting on the stage.” How very true! In ancient Greek theatre, the chorus actors were the ones producing the earthquake effect in The Bacchae when Dionysus brings down Pentheus’ palace. Since the first satyr dithyramb to modern times, Euripides’ scenic poetry has been created by the movements of an actor’s body in which there has always been “a piece of Dionysus.”

Slavko Milanović

THE BACCHAE FIRST TIME AMID THE SERBS

After the unsurpassed Medea, The Bacchae are probably the most often performed, translated and commented one of all Euripides’ plays. The cause is not that this is the play written last by “the naughty boy” of Athenian drama; moreover, the popularity of the drama had been reinforced by circumstances the play was written in, brought back and performed in Athens. The Bacchae was written abroad, at the court of Archelaus, the King of Macedonia, near today’s Strumica. The poet went to exile at the very end of the Peloponnesian War, most probably in 408 BC, because he found out that he too had been charged with corruption of young Athenians, which at the time was quite enough for a sentence to death by poisoning with a well-known Athenian poison, the hemlock. In order to evade this destiny, he silently went to an exile inland, a far inland when the Greeks are concerned, where winters are much harsher and where there was no Athenian snobbery and where the manners of all, including the King Archelaus himself, are more down to earth. In these circumstances, only a year or two before his death, Euripides writes his last two plays: Iphigenia in Aulis (also performed in the National Theatre) and The Bacchae. Shortly after his death, a relative takes these two plays back to the ungrateful homeland, which finally sees that the intrigues and gossip have banished its most talented playwright. Euripides’ cousin funded staging of the plays and the audience’s exaltation was such that tears were allowed in public for the first time in theatre …Such a drama – the most humane and the most savage one ever written by the Euripides – is followed by its spokesperson fama. She is responsible that the play has survived to the day, as well as for its translations and performances in many countries throughout the world and, finally, for literature about the play, which surpasses the play’s modest volume by hundreds of times. However, it was a pure chance that the play was not translated into Serbian until 2006. The Translator does not know the reason this happened, but he knows that he felt both privileged and perplexed that there was to be the first and, so far, the only translation of the play into Serbian (as much as 2400 years after it was written and at least two hundred years after it was translated to other languages). The translation is being performed at the National Theatre’s stage, but we need to say a couple of words about its necessary scenic adaptations. A play cannot be staged without certain abridgements and changes, and it is the case with this play as well. We need to state that the chorus of Tmolus women has been divided into parts for four choristers named by the director Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta. In addition, there is quite a long part of the text (62 trimeters) written by the famous British translator and Hellenist Philip Vellacott. Vellacott wrote this text in order to fill one of the largest gaps in the play, in the most dramatic place at the end, when Agave after having dismembered Pentheus, her son, speaks about rebuilding his body from severed limbs.As a translator, I was aware of this lyric interlude, which I find created with undeniably Vellacott’s literary preferences, but when the play was published (Euripides, Selected Plays, Plato, 2007) I did not use the interlude in the original text. The reason was that the interlude was written primarily in English, which means that only minor parts of the text were taken from Greek sources, and because I found that Vellacott, inspired by the Euripides, might have even “over-Euripidesized” this powerful drama situation and wrote something, perhaps, too pathetic. However, when asked by Staffan Valdemar Holm, the director, to look at Vellacott’s hyperbolic insertion again, I found that my opinion might have been too harsh and that the unquestionable beauty of the text and requirements of dramaturgy are sufficient reasons for its translation from English. Therefore, I did so. With some other minor changes and additions, the text was ready for stage. Everything else is, as it should be in a theatre, left to actors, the best ones – the Translator is sure – that work in the National Theatre.

Aleksandar Gatalica

Premiere performance

Premiere, February 19, 2010. / Main Stage

Translation from the Ancient Greek Language by Aleksandar Gatalica

Directed and adapted by Staffan Valdemar Holm, guest artist

Set and Costume Design Bente Lykke Moller, guest artist

Lighting Design Torben Lendorph, guest artist

Dramaturgy Slavko Milanović

Music Selection Staffan Valdemar Holm, guest artist*

Music Arrangements Vladimir Petričević

Speech Ljiljana Mrkić Popović, PhD

Simultaneous translation Serbian-Swedish Vesna Stanišić

Producers Borislav Balać and Milorad Jovanović

Assistant Director Ivana Nenadović

Assistant Set Designer Miraš Vuksanović

Assistant Costume Designer Olga Mrđenović

Premiere cast:

Dionysus Nenad Stojmenović

Tiresias Marko Nikolić

Cadmus Tanasije Uzunović

Pentheus Igor Đorđević

Messenger Slobodan Beštić

Agave Radmila Živković

Chorus:

Alpha Stela Ćetković

Beta Nela Mihailović

Gamma Jelena Helc

Delta Daniela Kuzmanović

406 BC/Title of the original BAKXAI

Organizer Barbara Tolevska

Stage Manager Saša Tanasković

Prompter Gordana Perovski

* Songs (arranged by Vladimir Petričevicć “I love Rock and Roll” (Jake Hooker / Allan Merril, Rak Publishing) and “Satisfaction” (Mick Jagger / Keith Richard, EMI & Essex) sung by Stela Ćetković, Nela Mihailović, Jelena Helc and Daniela Kuzmanović; and “Song to the Siren” (Larry Beckett / Timothy Charles III Buckley/ Third Story Music) is sung by Radmila Živković.

Sound Designer Vladimir Petričević

Assistant Lighting Designer Saša Popović

Lighting Master Vlado Marinkovski

Make-Up Designer Dragoljub Jeremić

Stage Master Zoran Mirić

Sound Master Tihomir Savić

Sculpturing by Stanimir Pavlović and Vladimir Simović

Puppet Design Radoš Radenković, Sculptor

Painting by Srđan Pušeljić and Ilija Krković

Special effects by Milan Alavanja

Costumes and decor were manufactured in the workshops of the National Theatre in Belgrade.