Road to Damascus

drama by August Strindberg

STRINDBERG - OUR CONTEMPORARY

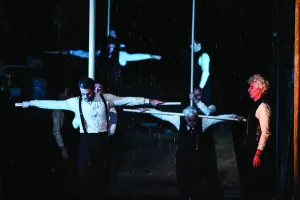

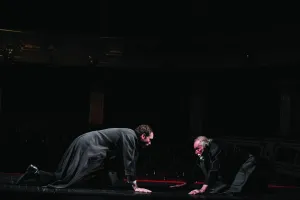

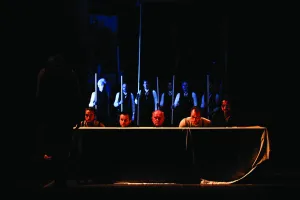

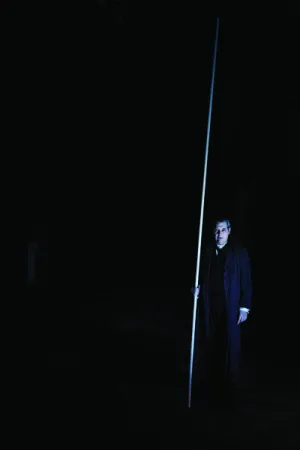

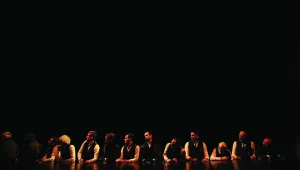

Đerđ Lukač, in his History of Modern Drama Development, speaks about the beginnings of naturalism as “great playwrights’ battle for a place on stage and against patterns which ruled the stage (…) Everywhere, in novels, poetry, art, music –expressions of new emotions in new forms and artistic values portraying quite specific traits of modern life became visible, except in the drama literature where everything remained the same.” Playwrights were constrained with theatres’ requirements to have auditoriums filled to capacity, and the formula for success had already been established: the “well-made play” designed to perfection by Eugene Scribe. Although Emile Zola, in his manifesto on naturalistic theatre, mocked the theatre which was not able to portray problems of a modern man, inertness of the established formula for civil drama prevailed. What had changed in the nineteenth-century man that could not be presented by drama literature? In the 1860s, liberalism and faith into individual have reached their climax in Europe and everywhere else. Hero of the time was a person who creates history, the self-made man of capitalism. This brought an individual into focus; and the same was endorsed by the upcoming revolt against church and authority of Christianity. Darwin’s book on origin of species from 1859 was a motivation for a new scientific approach, which made an individual deal on his own with his status in life, even if it meant negation of the almighty God. Relationship between faith and science, with a focus on ethical responsibility of an individual and contemplation on personality and psychological “learning about soul”, which encompassed interest for imagination and mental problems, contributed to abandonment of universal to the benefit of individual man. The approach was presented in Scandinavian tradition as “series of touches by hand” from a teacher to student – from Kierkegaard to Ibsen, from Ibsen to Strindberg… There were discussions on the need to separate faith and knowledge into two absolutely independent categories. In such circumstances, everything was prepared for Nietzsche’s declaration on the death of the God, which made the irresistible responsibility given to an individual, to take a stand towards basic values in life, to pinnacle. Henrik Ibsen was the first one to respond to the challenge with his invitation for “closer ties between art and moral” (U. Eco) and introduction of intimate themes on stage, which were considered irrelevant until then. Ibsen, however, remained within the framework of firmly conventional civil drama. It was still necessary to have a new person to express inner confrontations in a new individual. Then August Strindberg appeared on European stage, Lukač described him as “a true Viking, tough, persistent and violent (…) He unrelentingly took every issue to its resolution, he liked to fight and he was looking for a fight (…) He possessed a revolutionary nature which changed everything he touched”. In Lukač’s opinion, it was his character and his active and adventurous spirit, which was ready to remain outside all literary approaches and to renounce all traditions without consideration, were Strindberg’s assets when compared to his contemporaries who also fought for new drama. If we should sum up the essence of Strindberg’s contribution to development of new form, we could say that it is his innovative understanding of dramatic characters. In the preface to his Miss Julie, he says that he made his characters “rather ‘characterless’”, because, as he says, his “souls (or characters) are conglomerates, made up of past and present stages of civilisation, scraps of humanity, torn-off pieces of Sunday clothing turned into rags – all patched together as is the human soul itself”. According to Elinor Fuchs, Strindberg has realised that creation of typical and “automatic” characters was the result of adhering to Aristotelian principle that “story (plot) is the soul of tragedy”. In Scribe’s well-made play, there was no place for Strindberg’s complex and unpredictable characters that “split, double, multiply, vanish, intensify, diffuse and disperse.”(from A Dream Play) The source of the “discovery” may be found as much in Strindberg’s personality characterized by constant soul-searching, quests and wondering, as in the spirit of the time he lived in. Triumph of science and absolute of scientific facts that enchanted Strindberg (to such an extent that he initially started studying medicine) was fertile ground for a new and one of the most radical ideas, maybe the most radical in the history of literature – that the writer does not have the right to take the omniscient role. In a mock interview with himself (published as a preface to the novel The Son of a Servant), much before Joyce and Virginia Woolf, Strindberg stated that “the writer, with his poor and superficial knowledge about psychology, should never try to portray the well hidden soul of other people” and that “a man cannot know more than one life, his own,” quite in the spirit of scientific objectivity. Strindberg’s “know yourself” became an imperative he adhered to all his life. All of his works (except, of course, his history plays) contain autobiographical elements. The autobiographical elements are not hard to find even in plays written after the so-called “inferno phase”, when he abandoned the naturalistic method by discovering the new form of symbolic/expressionistic drama. In the first one of those plays, a comprehensive trilogy The Road to Damascus, the events are not realistic; they happen according to the logic of a dream, and words are part of a giant soliloquy by the main character – the Stranger. However, the experts on his work (for instance Egil Tornqvist, Carl Dahlstrom, Göran Stockenström and others) find that every scene from the play can be traced back to a real event from Strindberg’s life, and even to actual place where the event happened. According to Slobodan Selenić, with this approach, Strindberg had entered “the dangerous place, defined by Breton as an approach were authors place understanding of their own personality and soul searching before their own work.” For Strindberg, the dissolution of character, with dream-like plot, were logical steps in research of “the one life a writer may know” – his own. Keeping in mind that there were no means of expression in the naturalistic, yet classical dramatic form, in The Road to Damascus he turns towards the tradition of medieval morality, miracle and passion plays, which portray a character’s life as a journey, with stops represented by scenes in the drama. By trying to “interpret real life with spiritual methods”, he creates a new drama structure which changes the modern age theatre. In this sense, Göran Stockenström quotes O’Neill “Strindberg is a pioneer of everything modern in theatre”, while Elinor Fuchs (in her essay Strindberg – Our Contemporary) sees his influence all the way to Beckett and the new avant-garde of the 1960s, and beyond – to post-modern experiments in American “theatre of scenes” (Robert Wilson and others). We believe that the production by Nikita Milivojević, based on the first part of the trilogy, confirms that Strindberg is our contemporary indeed. When compared to the time when the play was written (1898), theatre developed its own stage language, which enables carrying out Strindberg’s experiments. Primarily regarding verbal component of the play, which Strindberg first understood as one of components of the overall theatre language, and then with the concept of space and intensive use of all stage potentials – from acting and movement, to music and light, even the use of authentic ambient of the National Theatre.

Slavko Milanović

AUGUST STRINDBERG (1849–1912)

AUGUST STRINDBERG (1849–1912)

Strindberg, a Swedish playwright, novelist and painter – let us name just his major activities – was one of the most original artists of his time. He often used to stop writing at the most successful moment and focus his attention onto something else, for instance studying Theosophy and Swedenborg’s teachings. Although he wrote over 60 plays, he dedicated only a small portion of his time to playwriting; Gunnar Brandell calculated that playwriting took about ten years of his life. During his either short or longer breaks from writing, he dedicated himself to painting, experiments with photography (he tried to capture the starlight on photographic paper and to make photo-portrait in authentic size), and in period between 1892 and 1896 to alchemical experiments. His research of alchemy had serious implications for his health; he was hospitalised and he experienced a severe psychological crisis, which was believed to be a total mental collapse (by our S. Selenić, for instance); however, others believed that this was his experiment with his own consciousness (Barry Jacobs). Many experts on his work believe that his journeys, even his infamous paranoia, were merely his means of creation, research of subconscious influence over the creative process. Thomas Mann summarized this by saying that Strindberg was “a man of ingenious changes of direction and departures”. He achieved national success after his novel The Red Room (considered the first modern Swedish novel) and at the age of thirty he became a leading radical intellectual. Strindberg became popular in Europe after the triumph of his master-pieces Miss Julie, The Father and Creditors in Paris and Berlin, but he experienced a three-year long “inferno-crisis” and a six-year abstinence from writing. When he resumed playwriting, it was quite a new Strindberg who left the naturalistic method and turned towards symbolism and new, expressionistic style. He wrote the key play of modern theatre – trilogy The Road to Damascus (first two parts in 1898, third part in 1901). In his final period he wrote in a new “dream plays” style, but also in naturalistic style, enriched by symbolism and religious tones. In this period, he returned to writing historical drama, the genre with which he started his playwriting career forty years earlier. Strindberg was the first naturalistic playwright who realized that the new drama requires the new theatre, a new and more intimate relationship between stage and auditorium and this is why, under the influence of Antoine’s Theatre Libre, he founded the first Scandinavian Experimental Theatre and, later on, the Intimate Theatre in Stockholm. Other important works by Strindberg are: dramas – Master Olof (first great success 1872-1877), The Dance of Death (1900), A Dream Play (1901), The Ghost Sonata, The Pelican (1907); novels – The Son of a Servant (1886), Legends (1897), Inferno (1897), A Madman’s Defense (1876), collection of stories Getting Married (1884, translated into Serbian as Marriages)…

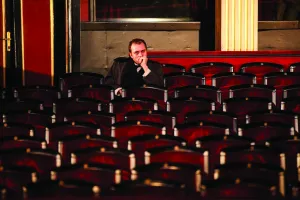

NIKITA MILIVOJEVIĆ is one of the leading Serbian stage directors today. “He has made a mark in Serbian theatre of the 1990s with engagement of his plays; with his bold and innovative understanding of the classics, he introduced the Serbian theatre into the new century.” Jovan Ćirilov

NIKITA MILIVOJEVIĆ is one of the leading Serbian stage directors today. “He has made a mark in Serbian theatre of the 1990s with engagement of his plays; with his bold and innovative understanding of the classics, he introduced the Serbian theatre into the new century.” Jovan Ćirilov

Milivojević received all relevant theatre recognitions for directing in our country: “Bojan Stupica” Award, Sterija Awards for Best Director, BITEF Award, Award of the Critics of the “Scena” Theatre Magazine; and annual awards of the National Theatre in Belgrade, Yugoslav Drama Theatre, Budva City-Theatre, National Theatre “Ljubiša Jovanović“, Šabac. He also won awards at numerous festivals in Kragujevac, Vršac, Novi Sad, Šabac, Ohrid Summer Festival in Macedonia, etc. In an opinion-poll amongst Serbian theatre critics, his production of Banović Strahinja has been declared the most important production of the 1990s in Serbian theatre. Since 2000, he has been building a career abroad. He directed in Greece, Sweden, Slovenia, Macedonia, Turkey, Germany, Italy, Cyprus, USA, etc. (Calderon, Shakespeare, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Chekhov, Bulgakov, Pinter, T. Mann, Brecht, H. Miller, Ruzevich, Vitrak, Ionescu, Bond, Beckett, Stoppard, Maeterlinck, Sartre, Wilder, Ibsen, Strindberg…) Milivojević wrote the script and directed the film Jelena, Katarina, Marija, based on the novel New York – Belgrade by D. Miklja. He was a director of the Bitef Theatre and BITEF festival in period 2005-2009. Since 2009, Milivojević has been working as a Professor at the Academy of Arts in Novi Sad, Department of Acting/Directing. Milivojević lives and works in Belgrade.

AMALIA BENNETT

AMALIA BENNETT

She graduated from The Laban School for Movement and Dance in London. Since graduating she has been living and working in Greece. From 1993 till 2008 she worked as a dancer and assistant to the choreographer Kostandinos Rigos. Since 2000 Amalia has been working as a freelance choreographer in the theatre in productions mainly for the National Theatre in Thessaloniki and Athens. She has also worked in China, Canada, Germany, Sweden, Macedonia, Turkey, Cyprus, USA … She has been teaching movement for actors since 1996 in The National Theatre Academy in Athens and Thessaloniki and in The Athens Conservatory for Music and Drama. Amalia has been collaborating with director Nikita Milivoјević since 2002.

Premiere performance

Premiere 22th November 2014 / Main stage

Stage Director, Adaptation and Conceptual Design of the Set Nikita Milivojević

Stage Movement and Conceptual Design of the Set Amalia Bennett

Dramaturge Slavko Milanović

Costume Designer, Puppets and Masks Designer Marina Vukasović Medenica

Composer* Zoran Erić

Speech Instructor Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Producer Milorad Jovanović

Assistant Director and Organiser Ivana Nenadović

Painting on costumes and puppets Marija Tavčar

Set Design Realisation Miraš Vuksanović and Jasna Saramandić

*Music selection (J. S. Bach, St. Matthew Passion; Nils Frahm, Said and Done) Nikita Milivojević and Amalia Bennett

Premiere Cast:

The Stranger, Caesar Hadži Nenad Maričić

The Lady, Mother Sena Đorović

The Stranger, The Doctor Boris Pingović

The Stranger, Landlord Nebojša Kundačina

The Stranger, Čvorak Bojan Krivokapić

The Stranger, Caesar Pavle Jerinić

The Lady Jelena Đulvezan

The Stranger, The Beggar Branko Jerinić

The Lady, Mother Aleksandra Nikolić

The Stranger, The Beggar, The Old Man Tanasije Uzunović

Extras: Božidar Katić, Dragoljub Denić, Miloš Dmitrović, Stanko Đalić, Vojislav Obradović, Aleksandar Vukić, Slaven Radovanović, Milan Gerdijan, Zoran Trifunović, Milan Šavija

Stage Manager Sandra Žugić Rokvić

Prompter Gordana Perovski

Light Operator Miodrag Milivojević

Make-Up Dragoljub Jeremić

Set Crew Chief Zoran Mirić

Sound Operator Perica Ćurković

Sets were made in the National Theatre’s workshops under supervision of Goran Milošević

Costumes and shoes were made in the National Theatre’s workshops

Male costumes’ designer Drena Drinić

Head of male costumes tailor shop Jela Bošković

Female costumes’ designer Radmila Marković

Head of female costumes tailor shop for Snežana Ignjatović

Shoe designer Milan Rakić

Head of shoemaker’s shop Žarko Lukić

Translations by Ljubica Topić, Zlatko Matetić and Božena Matetić were used for the adaptation