Falstaff

opera by Giuseppe Verdi

VERDI’S DREAM THAT CAME TRUE ABOUT “FALSTAFF”

Everything is chattering and everything runs in a swirling flow; continuous musical recitative; the orchestra is used with a lot of spirit and feeling for vivid colours; a joke, a pun, light humour, a grotesque in continuous flow; the weaving of the ensemble is extraordinarily intricate; the entire score is a sound filigree network... These fragments from the texts of Miloje Milojević, Milenko Živković and Pavle Stefanović, written in 1940 on the occasion of the Belgrade premiere of “Falstaff”, are the best testimony to the composer’s joy of creation, who is already in his 8th decade of life and who is finally composing a comic opera (for the second time in his life).

For the faithful opera audience for whom Verdi’s name is often synonymous with the opera art itself and who know by heart the arias and duets from “Il Trovatore”, “La Traviata”, “Rigoletto” or “Aida”, “Falstaff” will be something completely different from what they heard until then.

From Verdi’s letters one can really see with what delight he worked on “Falstaff”, writing it “for his own pleasure”. His second work in his career (after his first opera “Oberto” in 1839) was the comic opera “Un giorno di regno” (“King for a Day”) (1840) which unfortunately did not go well and although it is believed that after that failure Verdi no longer wanted to return to this genre, he actually waited all his life for a good libretto.

It finally arrived with the composer and librettist Arrigo Boito (1842 - 1918). Music publisher Giulio Ricordi introduced Verdi to Boito trying to motivate Verdi, who after “Aida” decided not to compose any more new works. Boito’s idea to offer the composer texts based on Shakespeare’s works boosted Verdi’s inspiration because Shakespeare was one of his favourite poets (“I have been reading him over and over again since my early childhood”). In addition to the opera “Macbeth”, performed in 1847, Verdi “sketched” “King Lear” and wanted to compose “Hamlet”. Verdi and Boito’s first collaboration was on the opera “Othello” (1887), which was a great success and the composer, who was 74 at the time, thought it would be a nice end to his career. However, Boito suggested that he also write a comic opera whose protagonist would be one of the “most popular comic characters in all of English literature” - Falstaff. Boito writes to Verdi that there is an even better way to finish his career, and that is to astonish the world with a mighty burst of laughter. Verdi finally agrees, not guaranteeing that this opera will ever see the light of day, but, enthusiastic about the subject, will write it for his own pleasure.

Shakespeare found inspiration for the character of Falstaff, among other things, in folk festivities he attended since childhood. Festivities that mark significant dates in the life of a community date back to the Archaic period. They gather and unite people through song, dance, rituals, mythological performances, costumes and masks and are the source for the creation of theatre in general. According to Stephen Greenblatt, Falstaff is the counterpart of the Lord of Misrule (the ruler of certain festivities) who turns the established social order upside down. The festivities he led allowed rebellion, overstepping of boundaries, disobedience and wanton behaviour, however, everything would return to order after they were over. Wearing costumes and masks was implied, and under the mask anyone could be someone else, at least for a moment, and even a beggar could become a king. Costumes often overemphasized the physical features of a person in the form of long noses or big bellies and added to the character’s personality. That’s how Falstaff got his recognisable corpulent silhouette, but also his incorrigible character, by which the theatre audience will immediately recognise him in any play he may appear. And in Shakespeare he appears in “Henry IV” (Part I, 1596-97), “Henry IV” (Part II, 1597-98), in “Henry V” (where his death is mentioned, 1599) and “The Merry Wives of Windsor” (around 1597-1601). According to legend, the last one was created at the request of Queen Elizabeth I, who wanted to see how Falstaff, with all his qualities, would manage in the role of a lover. A cowardly knight, a drunkard, an opponent of moral principles and any authority, endowed with ingenuity, wit and the ability for beautiful expression could only become a false suitor who respects his own rules and pursues his own interests. But, being moved from a historical to a civil play, Shakespeare’s famous character can no longer cope in a new environment and a new social class, and this time he is the one who is deceived.of action and music represent an important characteristic of musical dramaturgy, and on the other hand, for the sake of contrast, lyrical moments are present “embodied in a young couple who will find their happiness after overcoming a series of obstacles”. In this case it is Nannetta and Fenton whose sincere feelings are a contrast to Falstaff and his idea of love.

Their short duets are the thread that connects the entire opera, which is how Boito put his idea to practice when he said: “I would like to sprinkle the entire comedy with that happy love, just as someone sprinkles sugar on a cake.” In the notes for the performance of this opera, which he defines as a lyrical comedy, Verdi drew attention to the fact that it must be sung in a different way from previous comic operas, with movement on stage and a lot of running.

For Verdi himself, Falstaff is a rascal who does various mischief, but above all he is funny. Alice, Meg, Mistress Quickly, and Nannetta throughout the opera are trying to stop him from deceiving others. At the same time, Alice wants to mock her husband Ford’s unreasonable jealousy, and also to get Nannetta and Fenton married without adhering to the customs of the period, i.e. arranged marriages.

The final scene with Falstaff disguised as the Sable Huntsman, fairies and witches, with the mistaken identity and the culmination that brings the final punishment to Falstaff carries the elements of a festivity which, according to tradition, before restoring order and return to everyday life, often ended with a feast to which the main protagonist would take those present with Ford saying – “It’s Falstaff’s treat”. Verdi ends the opera with, as he called it, a “comic fugue” whose thematic material, according to Budden, is “extracted from the heart of the opera”, with the words “All the world’s a jest” and “He who laughs last laughs longest”.

The premiere of “Falstaff” took place at La Scala in Milan on February 2, 1893, during the carnival season (just as the premiere of “Aida” in 1872, for example, was performed during the carnival season). It was a national event attended by correspondents from all over Europe, and the audience included the Minister of Education, the playwright Giacosa, the painter Boldini (the author of one of Verdi’s most famous portraits) and the composers Puccini and Mascagni. The success was complete.

On a note that was found many years later in the score of “Falstaff”, Verdi said farewell to his hero, the “old humorous guy”, sending him off to the world of theatre where, in various guises and in its many forms, at all times and everywhere, he would be “forever true” Falstaff.

Arrigo Boito, a great connoisseur of Shakespeare’s works, will create the opera character of Falstaff by combining the elements of the aforementioned plays, but he will choose “The Merry Wives of Windsor” as the basis of the play. Boito as an opera composer (known for “Mefistofele” in 1868) was quite familiar with the construction of the operatic work and wrote librettos for “Othello” and “Falstaff” which are considered to be the best texts ever written for Italian opera.

The close collaboration between Boito and Verdi on the opera librettos is evidenced by their vivid correspondence, and the result is two works that represent the culmination of Verdi’s creative work and Italian opera itself. The opera “Falstaff” is as specific to Verdi himself as it is to opera art as a whole. It represents a kind of bridge to modern music. According to Julien Budden, we can say that “Falstaff” starts a new tradition that will be reflected in Cilea’s “Adriana Lecouvreur”, Puccini’s “La bohème” and perhaps most of all in “Gianni Schicchi” - each of them pays tribute to it.

This work is not dominated by arias, duets or choruses, as in Verdi’s previous operas, but by ensembles, and as a whole it is conceived as one continuous flow. In this sense, “Falstaff” represents a completely new style of opera buffa, which basically has elements of this genre where, on the one hand, according to Nadežda Mosusova, ensembles as key factors in the development.

Vanja Kosanić

A WORD FROM THE CONDUCTOR

“Tutto nel mondo è burla. L’uom è nato burlone.”

“Everything in the world is a joke. The man was born a prankster”, is the final message of Verdi’s and Boito’s Falstaff, which is announced by all the protagonists, with an additional conclusion – Everyone’s (we are all) gulled!

However, a joke also hides a deception, a hoax, a prank, a ruse, a farce...

After a number of difficult and “bloody” librettos that allowed him to manifest his musical genius, in his later years Verdi turned to a more cheerful genre and Shakespeare’s most popular anti-hero, whose features, actions and thoughts, as well as the characteristics of other protagonists, we recognize as timeless, still present and contemporary.

Falstaff’s faults are countless. Nevertheless, he is neither ashamed nor denies them. On the contrary, in his “Indian summer” he tries to get everything he can from life, feeling the relentless transience, scorning and dismissing social conventions and higher ideals. Wrapped in a joke and comic genre, the eternal questions of meaning and human nature lie before us to which humanity has been trying to give an answer since the dawn of time. Verdi’s testamentary answer is given by the choice of this libretto, through laughter and sneer.

It is no coincidence that Falstaff was the preferential choice of a significant number of reputed conductors, accomplished through interpretations of the most intricate symphonic scores and musical dramas.

The musical layers that Verdi placed in Falstaff are the result of his entire life experience, leaving the melodic and harmonic attractiveness and predictability to great extent in his own past, going towards unexpected solutions and an expression that was not characteristic of him until then. In a seemingly very solid, rhythmically unrelenting musical creation, there is a great possibility of freedom of expression for each protagonist on stage as well as for the orchestra, so the disclosure and understanding of as many given layers as possible is exactly the inspiration for every conductor, including me.

For the ensemble of the National Theatre in Belgrade, each rehearsal meant the unveiling of new possibilities for the interpretation of Falstaff in many details, and I believe that this process will continue in later performances of this opera, both for the protagonists and the audience.

Casting top singers in two or three main singing roles ensures the success of the entire performance in a significant part of the stringent opera repertoire, as well as the interest of the audience that is prepared to ignore some shortcomings in other segments of the opera production because of the appearance of a particular star. Verdi’s Falstaff does not offer such an opportunity, but it rather shows the strength of the author team and the entire ensemble, having no less important link in the production.

From the very beginning of the opera, Verdi draws us into a musical whirlwind accompanied by frantic events on stage, which does not stop until the final fugue of this burlesque. As the work on Falstaff progressed, it got under our skin more and more, and it was remarkable to see how the initial insufficiently comprehensible segments gradually fit into the ingeniously designed musical and scenic puzzle of the unsurpassed maestro Verdi.

Falstaff is a provocation and a challenge, both for the protagonists and for the audience - with its speed of action, sharpness of wit, openness to numerous possible morals and meanings. Therefore, in addition to opera connoisseurs and faithful followers, I also expect to see some new, intrigued audience, eager for novelty.

Belgrade Falstaff is all that.

WHAT MAKES AN OPERA A COMIC OPERA

A WORD FROM THE DIRECTOR

So, what makes it comic?

Probably the fact that everyone in it keeps changing clothes with the intention of upsetting other characters, taking revenge, cheating on the spouse or getting their hands on someone’s wealth.

This type of a play is most often called a comedy of errors, which is also the case with some of Shakespeare’s plays. Among them is the play The Merry Wives of Windsor, which was the main inspiration for Giuseppe Verdi’s last opera.

“Comedy of confusion and errors”, as the description of the genre, is what strikes the nerve in Falstaff, and precisely where it hurts the most: the title character, victims and opponents, all dressed up and disguised, in back rooms and front yards, suggest that behind the chaos of mistaken identities lurks the abyss of human imperfection.

The entire plot of Falstaff is connected with excess: someone is too fat, another one is too poor, a third one is too in love, a fourth one is too jealous, and there are too many gullible, decrepit, too fainthearted people. Verdi’s panopticon, a vortex of body and spirit, reaches its climax in the finale:

“Everyone’s gulled,

Nothing but clowns everywhere

Each pokes fun at the other

But he who laughs last laughs longest.”

SUMMARY

ACT ONE

Part One: At the “Garter Inn”

Sir John Falstaff is sitting comfortably at his desk writing letters for two ladies. Dr Caius bursts in, shouting that the knight has broken into his property and maltreated his servants. Falstaff blandly admits to the charge, but proposes to do nothing about it. The enraged doctor accuses Bardolph and Pistola that they picked his pockets the day before. The offended Pistola threatens the doctor. Falstaff imposes order; then sits in judgment on the case: Dr Caius fell asleep under the table, dead drunk, and dreamed his money was stolen. Caius retreats, swearing that if he ever goes drinking again it will be with sober, law-abiding, pious men. Bardolph and Pistol mock him. But Falstaff is in no mood for horseplay. Silencing his followers, he turns to more serious matters: the landlord’s bill. He commands Bardolph to look into his purse, but all it contains is two marks and a penny. Falstaff unfolds his plan to resolve their financial predicament – he found a solution in courting rich ladies. There is a merchant in Windsor called Ford whose wife holds the purse-strings. Her name is Alice, she is beautiful and she favours old Falstaff. And there is another too, Meg Page; she too is hot for him. Pistola and Bardolph, however, refuse to deliver the letters Falstaff has written to these women. Bardolph loftily explains that his honour will not allow him. While the page-boy leaves with the letters, Falstaff turns wrathfully to his followers and gives a grand speech about honor. At the end his patience is exhausted and he sweeps Bardolph and Pistola.

Part Two: a town tavern

Falstaff’s letters have been delivered. Meg Page, accompanied by Mistress Quickly, hurries to Alice Ford to tell her about the letter, just as the unsuspecting Alice, with her daughter Nannetta, comes out of the house carrying hers. To their astonishment, the letters are identical. It provokes a gurgle of laughter from all. Then, as respectable women, they plot a revenge for Falstaff. Ford, Dr Caius, Fenton, Bardolph and Pistola enter, deep in conversation. Pistola is telling the horrified Ford about Falstaff’s designs on his wife and about the letters Falstaff has sent, which he and Bardolph refused to deliver. Ford must be on his guard, or he will soon find himself wearing a pair of horns. They all exit the stage and Nannetta and Fenton are left alone. The young lovers’ hurried conversation is cut short and they separate as merry wives and Mistress Quickly reappear. Alice instructs Mistress Quickly to go to the Garter Inn and offer Falstaff an assignation with him. The women are already looking forward to the punishment they are preparing for Falstaff. They disperse at the sight of a male figure nearby. It is Fenton; he and Nannetta briefly resume their mock warfare. Men re-enter the stage: Ford has decided to visit Falstaff at the Garter Inn under an assumed name and set a trap for him, in which Bardolph and Pistola will help him.

ACT TWO

Part One: at the “Garter Inn”

Falstaff drinking sack awaiting events. Bardolph and Pistol appear, full of (feigned) penitence. Bardolph ushers in the first visitor. It is Mistress Quickly who would like a word with Sir John in private. Falstaff graciously grants her an audience. She conveys a delicate message: Ford’s wife, who received Falstaff’s letter and is madly in love with him, can entertain him undisturbed from two till three. Mistress Quickly tells him that Meg Page also sends Falstaff a tender reply, but unfortunately her husband is rarely out of the house. He rewards her and she leaves. Falstaff rejoices. Bardolph enters announcing the second visitor – a certain Master Fontana who has brought with him as a gift a demi-john of Cyprus wine. Ford enters, in disguise. Ford relaxes, helped by a bag of gold which he dangles in front of the interested Falstaff, and comes to the point. He is in love with Alice Ford, but no matter how hard he tries, she remains indifferent and rejects his advances. Falstaff expresses his sympathy and together they recall the old song about love giving the lover no peace. Ford asks him to seduce Alice for him, in return for the money he has brought. If Falstaff can only break down her defences and pave the way for him, Master Fontana can follow. Sir John calmly accepts the commission as he has just had word from Alice that her boor of a husband will be out between two and three. Falstaff is going to put horns on him and begs Master Fontana to excuse him: he must now go and make himself beautiful for the assignation. Ford is now left alone and the appalling truth sinks in. His wife is deceiving him. He curses marriage, but vows to catch her and her lover in the act and get revenge on them. Falstaff returns wearing a new doublet and hat, they link arms and go out together.

Part Two: a room in Ford’s house

The merry wives have met to hear the result of Mistress Quickly’s mission. She announces that the trick has taken: the knight has swallowed the bait and will be here between two and three. Alice summons her servants to get everything ready, including the big basket of dirty linen which they are later to empty into the river. Then she notices Nannetta’s woebegone expression. The poor girl explains that her father wants to marry her to Dr Caius. Her mother promises that will not happen. Alice makes the final arrangements: the comedy is about to begin! Mistress Quickly announces Falstaff’s arrival and the women go hiding except Alice who sits at the table taking up the lute, strums a few chords before Falstaff comes. He enters eagerly, murmuring a song to the lute. Falstaff begins to press her close when Alice deflects him by a gentle allusion to his bulk, and he conjures a sparkling image of himself as a youth. Alice brings him down to earth. How can she trust him not to deceive her when he loves another – Meg? Falstaff brushes the idea aside contemptuously and take her in his arms. Just in time Mistress Quickly enters agitated: Meg is on her way there and in a rare state. Falstaff hides behind the screen just as Meg, choking back her laughter, enters crying that Ford suspects that Alice has a man hidden in the house and is coming to kill him. A moment later Ford is coming followed by a whole crowd of people. He yells at Alice and tells Dr Caius to search the house and he himself rummages frenziedly in the laundry basket. But it is empty and Ford storms out. As soon as Ford has left, Meg helps Falstaff to get into the laundry basket and piles some laundry on top of him. Unseen by anyone, Nannetta leads Fenton behind the screen where they embrace. Bardolph, Pistol, Ford and Caius arrive angry as they have found nothing. Suddenly, the sound of kissing is heard from behind the screen. All stop dead. They approach the screen and find Nannetta and Fenton there. Ford rages beacause he told Fenton a thousand times that Nannetta is not for him. Bardolph and Pistol call out that Falstaff has been seen on the stairs and they all go in pursuit. Alice summons her servants who, struggling with their mighty load, throw the basket out of the window into the river. Ford, who re-entered, is led by his wife to the window to join in the general laughter at the spectacle of Sir John Falstaff floundering on the Thames.

ACT THREE

Part One: at the “Garter Inn”

Falstaff is seated deep in gloomy thought. The innkeeper brings the mulled wine and at once his gloom is forgotten. His delight is interrupted by Mistress Quickly. In a volley of abuse he denounces Alice: for her treacherous sake he has almost drowned in the Thames. Quickly pacifies him with explanations, blaming the servants. Alice sent him a letter asking him to meet her in Windsor Park at midnight, at Herne’s Oak. Falstaff should come disguised as Sable Huntsman. He reads the letter secretly watched by Alice, Meg, Nannetta, Ford, Dr Caius and Fenton. Mistress Quickly tells him of the legend of Herne’s Oak and the two of them leave to talk in private. Alice tells the sinister story of Sable Huntsman. Meg and Nannetta confess they feel really frightened but Alice calms them telling them it is only a fairy-tale invented to make children go to sleep. They all make plans for the masquerade. Nannetta, in white dress and veil, will be Queen of the Fairies, Meg Nymph of the Woods, and Mistress Quickly a witch; boys and girls will dress up as imps and elves and they’ll set on the knight and make him atone for his wickedness. The women and Fenton disperse to make ready. Ford and Caius remain and plan for the doctor to marry Nannetta. Caius will recognise her by her white dress and at the end of the masquerade Ford will bless them as husband and wife. Quickli overheard this and decided to spoil their plan.

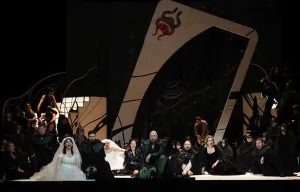

Part Two: Windsor Park

Fenton, first to arrive awaits the arrival of the others. Nannetta answers to his ecstatic love song hastening towards him. They are interrupted by Alice. Alice and Nannetta dress Fenton in a monk’s black robe and cowl and a mask. The knight’s footstep are heard and they exit the stage. Falstaff enters, with a pair of antlers strapped to his head, reflecting that even Jove took on the likeness of a bull for love of his Europa. A soft footfall is heard. It is Alice and he attempts to embrace her. No, whispers Alice, Meg has followed her. Well, he will have them both, said Falstaff. Meg calls in alarm: “The wicked goblins!” Alice and Meg disappears and Falstaff drops to the ground. The imps and fairies move slowly towards the Falstaff while Nannetta sings the fairie song. Suddenly Bardolph stumbles against Falstaff’s prostrate body. The imps and fairies jump all over him and roll his body about on the ground. Sting him, pinch him, stick him and prick him, the merry wives command. The man join in. The blows become more violent. When Bardolph, in the excitement of the moment, lets his cowl fall back, exposing his face, Falstaff turns on his tormentor, unleashing a torrent of abuse on that ignoble “salamander”. Alice and Meg take off their masks . Before Falstaff can recover from his astonishment, he sees Mistress Quickly and understands everything. The whole company join in and jeer unmercifully. But, Falstaff now rises from the ruins of defeat: he may have made an ass of himself, but without him, they wold be dull and savourless. Mistress Quickly takes Bardolph to change. The wedding of Nannetta and Caius is in order witch Ford announces. Dr Caius leads a veiled Queen of the Fairies by the hand, not knowing it is Bardolph in disguise. Alice introduces Fenton, masked, and Nannetta, concealed beneath a veil. Ford affably gives a blessing on both couples. We witness a double deceit. Ford is furious but he has resign himself to the inevitable fate and invites everyone to dinner with Sir John Falstaff. Then Falstaff launches the fugue - “Tutto nel mondo e burla” (All the world’s a jest) and the party continues culminating in an immense uprush of high spirits.

FALSTAFF ON THE NATIONAL THEATRE STAGE

The opera Falstaff was first performed at the National Theatre in Belgrade on January 26, 1940. The premiere performance, according to Miloje Milojević (“Politika” newspaper), was an event of great importance because this opera was “a work of art made of problems, and it is always a credit to those who advocate solving problems in art” which, according to him, also meant raising culture to a higher level. The performance as a whole left a “wonderful impression” on Milojević because it was well equipped and properly executed. Milenko Živković (“Vreme” magazine) reviewed the performance of the soloists and the orchestra (which played brilliantly) as extremely positive.

The conductor was Mirko Polič, the director was Dr Erich Heckel, set designer Mladen Josić and costume designer Vladimir Žedrinski. The libretto was translated by Stanislav Binički. The role of Sir John Falstaff was played by Milan Pihler, Ford - Alice’s husband was Rudolf Ertl, Fenton - Aleksandar Marinković, Doctor Caius - Slobodan Malbaški, Bardolph - Ćiril Bratuš, Pistol - Aleksandar Tucaković, Mistress Alice Ford - Bahrija Nuri Hadžić, Nannetta, her daughter - Anita Mezetova, Mistress Quickly - Evgenija Pinterović, Mistress Meg Page - Branka Bojović, Falstaff’s page - Miss Milbaher, Landlord - Ranisavljević, Guard - Stanišić.

The show was in the repertoire only in the 1939/1940 season and it was performed a total of 6 times.

The next production of Falstaff at the National Theatre premiered on October 7, 1978 and was performed within the Belgrade Music Festival (BEMUS). Mihailo Vukdragović (“Politika Ekspres” newspaper) wrote that the performance of Falstaff was an absolutely rare achievement that brought back memories of the “golden years” of the Belgrade Opera ensemble. The performance, which was characterised by the unity that connects “all threads of the complex opera organism”, was welcomed by the audience with unreserved sincerity and honesty. Director M. Sabljić adapted the stage movement to the music flow, and the light, bright-coloured set design and appropriate costumes contributed to the positive impression.

Dušan Miladinović was the conductor, Mladen Sabljić directed the opera, Miomir Denić was set designer, Ljiljana Dragović designed the costumes and masks, and Jovan Despotović was the choreographer. Dušan Popović played the role of Sir John Falstaff (alternating with Nebojša Maričić); Ford – Nikola Mitić (Velizar Maksimović); Fenton – Milivoj Petrović; Doctor Caius – Rajko Koritnik as guest (Tomislav Reno); Bardolph – Vojislav Kuculović as guest (Ivan Pavišić); Pistol – Aleksandar Đokić (Franc Javornik as guest); Mistress Alice Ford - Olga Đokić (Zlata Ognjanović as guest); Nannetta - Gordana Jevtović (Svetlana Bojčević); Mistress Quickly – Breda Kalef; Mistress Meg Page - Tatiana Slastjenko (Nada Sevšek as guest); Landlord – Tomislav Kaica.

That year, the National Theatre Awards were presented, among others, to Dušan Popović for his interpretation of the role of Falstaff and the show’s conductor, Dušan Miladinović, while the entire ensemble of the opera received the National Theatre Commendation. The National Theater achieved success with Falstaff on tour in Zagreb, Odessa and Moscow in April 1979.

The opera was in the repertoire until the 1980/1981 season and it was performed 16 times in total.

Vanja Kosanić

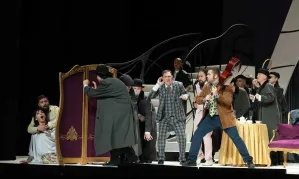

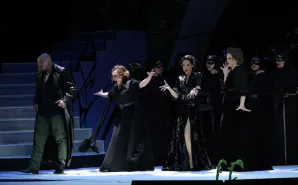

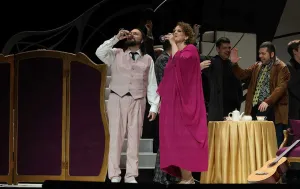

Premiere performance

Premiere, June 3, 2023.

Main Stage

Giuseppe Verdi

Falstaff

Opera in three acts | Libretto by Arrigo Boito

First performance in Milan’s Scala, February 2, 1893.

Conductor Bojan Suđić

Director Nebojša Bradić

Set Design Geroslav Zarić and Vladislava Munić Cunnington

Costume design Marina Medenica

Choreographer Isidora Stanišić

Producer Marija Kovačević

Professional associates Ivana Dragutinović Maričić and Ana Grigorović

Sir John Falstaff Nebojša Babić / Miodrag D. Jovanović

Fenton Siniša Radin / Mladen Prodan*

Dr Caius Aleksandar Dojković / Slobodan Živković

Bardolph Darko Đorđević / Stefan Živanović*

Pistola Mihailo Šljivić / Vuk Matić

Miss Alice Ford Sonja Šarić / Katarina Jovanović

Ford Dragutin Matić / Vladimir Andrić

Nannetta Snežana Savičić Sekulić / Vesna Đurković

Mistress Quickly Sanja Anastasia / Nataša Jović Trivić

Miss Meg Page Dragana Popović / Anastasia Stanković*

Choir, orchestra and ballet of the National Theater in Belgrade

Head of choir Đorđe Stanković

Concertmaster Edit Makedonska / Vesna Janssens

Assistant costume designe Ivana Mladenović

Assistant conductors Đorđe Stanković, Nina Fuštar, Jelena Miljević

Stage Manager Ana Milićević / Dušan Đorćević

Prompter Kristina Jocić / Nina Fuštar / Jelena Miljević

Music Rehersal Associates Srđan Jaraković, Nevena Živković, Nada Matijević, Vladimir Vanja Šćepanović, Aleksandar Brujić

Choir Rehersal Associates Tatjana Ščerbak Šandorov

Extras led by Zoran Trifunović

* Student of the Opera Studio “Borislav Popović”

Lighting operater Dragan Kolarević

MakeUp Marko Dukić

Stage Crew Chief Nevenko Radanović and Zoran Mirić

Tone operater Perica Ćurković

Video audio production by Petar Antonović

Assistant costume designer Ivana Mladenović

Costume and decor are made in the workshops

of the National Theater in Belgrade