Banović Strahinja

ballet to the music by Ivan Ilić

A WORD FROM THE DRAMATURG

“Forgiveness or Punishment?”

"Strahin was ban of Banska that by Kosovo doth stand; And such another falcon there is not in the land."* Already with the first verses of the ballad that has remained recorded as one of the most significant epic poems of the Serbian folk literature, the gusle player, Old Milija, suggests how remarkable the protagonist is. At the very end, his remarkability is emphasized again with the verses "scanty are the heroes as gallant as the ban". The opinion about the uniqueness of not only the protagonist, but also the ballad as a whole, the psychological aspect of the characters, the beauty of the language, was widely shared by the cultural public of Europe. The ballad came to limelight during Romanticism when national folklore and heritage were the main fields of interest for intellectuals. Thus, "Banović Strahinja" attracted the attention of one of the most prominent figures of German literature and European Neoclassicism and Romanticism in the late 18th and early 19th century, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who was ardently committed to detailed analysis, reflection and interpretation of the ballad. However, the ballad lives on and does not falter even in the 20th century, when it became and inspiration for many artists to create their works: a play (by Borislav Mihajlović Mihiz), a feature film (directed by Vatroslav Mimica, with Franco Nero, Dragan Nikolić and Sanja Vejnović in the main roles), a sculpture (by Ivan Meštrović). In the choreography of Lidija Pilipenko, in 1981, to the music of Zoran Erić, the poem that Vuk Stefanović Karadžić recorded after listening Old Milija singing it to the accompaniment of the gusle came to life through music and movement on the stage of the National Theatre. And, at the end of the day, it is where it returns again today, with a new score, choreography and libretto.

The vitality of the poem "Banović Strahinja" lies in the nuances and layers impossible to cover in one short dramaturgical note, but the main feature that still inspires adaptations today is the room Old Milija leaves in his narration for the psychological interpretation of the characters and their often atypical actions. First of all, it is unusual that Strahinja gives pardon unto his wife, who is unnamed in the poem, in times when it was customary for adulteresses to be "tied to horses' tails" and quartered. Let's just remember that Yug Bogdan and nine Yugović brothers, i.e. the father and brothers of Strahinja's wife, make the merciless decision to dismember her with knives, which Strahinja stops them from doing. Old Milija does not give us a definitive answer to the question why Strahinja acted against tradition. The answer remains open and subject to interpretation, and yet, it is important to be mindful not to succumb to the stereotypical, unequivocal reading that Strahinja "forgave" his wife. Let's not forget that she wanted to take his life, and yet he spares hers. Namely, the verses of the poem saying "but I have given my pardon" suggest the gift of life, but not necessarily forgiveness ; it is an important distinction that, with a little elaboration, leaves room for the question of what kind of life awaits his wife in a union with a man she does not love, especially considering that the woman is in a passive, submissive position - which reflects the difficult position of women in a given historical moment. Despite her high social status, she only functions as a hero's attribute (in addition to the falcon, sabre, greyhound, horse), she does not have her own voice, just as she does not have a name. The only thing we get as an indication from the poet about the wife's character, when she leaves with Vlah Aliya, is in the following verses: "All womankind are lightly led astray/ she leaped and grasped a splinter…."* In other words, there is no possibility of love or choice, she was simply carried away and deceived, and did not know what she was doing, so it was up to the hero and his assistants (by the way, unlike the wife, the greyhound Karaman and the horse Djogo are both mentioned by name in the ballad) to save her, both from delusion and from death.

A similar interpretative space that exists in thinking about Strahinja's motivation also exists in other characters: Angelia's betrayal may have been done out of love for Aliya, and perhaps also out of the awareness that her very contact with the Turkish army marked her as unfit, as an adulteress for whom there is no more life among her own; Aliya's plundering and kidnapping of Angelia can be "justified" by historical circumstances, in the sense that it was nothing unusual for the Turkish army that was occupying Serbian territories at the time... Therefore, there is room for psychological nuance, for humanisation and "justification" of human weaknesses and virtues in a non-romanticised manner, atypical for epic "heroic" literature and that period. With each verse, there is a new twist and deviation from the expected. Strahinja is an honourable and revered hero, but he is also someone who slaughters Vlah Aliya slitting his throat with his bare teeth (a far cry from the stereotypical heroic duel). The character of the old Dervish is one of the most striking examples of the twists and turns that the ballad has in abundance. The Dervish, who was once Strahinja's prisoner and was granted freedom, now becomes the only one who helps Strahinja in his search. Again, a twist and the deviation from the expected: the only ally our hero has comes from the lines of his foes; and those who are closest to him, the Yugović brothers, glorified iconographic heroes, turn their backs on him when he needs them the most.

In our interpretation of the poem, the main dramaturgical technique was to search for the most noble motivations of the characters, essentially melodramatic. For example, the wife, Angelia (a name that appears in other, mentioned adaptations) first leaves with Vlah-Aliya to save other lives at Strahinja's court, and later falls in love with him; Vlah-Aliya does love Angelia, but he is on the opposing side due to historical, wartime circumstances; Banović Strahinja pardons Angelia and gives her the gift of life because, in fact, he forgives her, and in the end they find a common language of love. That is why "our" Strahinja, from our version of the story, is special precisely because at the very end he understands and respects the freedom of choice, which stands out as the ultimate value that makes us beings capable of love and forgiveness.

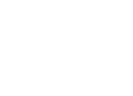

In our adaptation, we introduced the character of the Narrator, who is present throughout the entire ballet as Strahinja's discreet companion, in different forms, both as his faithful servant Milutin, as the Dervish, but also as a voice that symbolically guides Strahinja not only through his quest, but also through the centuries. He is the personification of the voice of folk heritage and mythology that continues to live in the modern time.

Đorđe Kosić

*Translator’s note: Verses of the ballad “Banović Strahinja” translated into English were quoted from the book HEROIC BALLADS OF SERVIA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH VERSE by George Rapall Noyes and Leonard Bacon

A WORD FROM THE COMPOSER

As a great admirer of our musical tradition, I knew from the moment I started working on the score for the ballet “Banović Strahinja” that it must contain the elements and overtones of our native musical tradition. However, I also wanted to convey that the piece was composed in the 21st century, to be imbued with the musical motifs of different characters and situations, and to give this almost cinematic score practically a symphonic colour. The overtone of tradition is really only an overtone because the given themes are not quotations, but they were written in the traditional spirit. It is just one segment of the style that I chose, or that the work itself imposed on me. The second is certainly the desire to write themes that could transpose through the different feelings of the characters, which are imposed on them by the situations in which they find themselves. The themes of Banović Strahinja, Vlah-Aliya, the love theme of Angelia and Strahinja, as well as of Angelia and Vlah-Aliya gradually develop and build, as their relationships transform. The theme of the Narrator/Dervish/Fate is equally important for the entire course of the work because it keeps bringing us back to the original path of spiritual quest and a personal path that is constantly changing, but remains recognizable. The themes of Banović Strahinja’s mother and the Yugović brothers are also significant as they contribute to a better understanding of the mentality of our people back then.

In addition to the entire orchestra, the score also includes solo parts for traditional instruments such as flute and kaval and traditional percussion instruments. The score also contains a special treatment of the English horn, because in some numbers it should be played with the addition of a distortion effect (guitar distortion) in order to evoke the sound of the zurna. Numerous sound effects are also present.

To be a part of such a complex project represents a great challenge but also a privilege, because we leave a mark in the body of the entire national cultural being. The work is, on the one hand, infused with the national spirit, and on the other, with deep personal and emotional turmoil. All the characters achieve catharsis, but they remain consistent with their inner self despite the major changes that surround them and are imposed on them by the confluence of external circumstances.

Ivan Ilić

LIBRETTO

“BANOVIĆ STRAHINJA”

PROLOGUE: The narrator introduces the story of Banović Strahinja, Angelia and Vlah-Aliya, indicating their inextricable intertwined destiny.

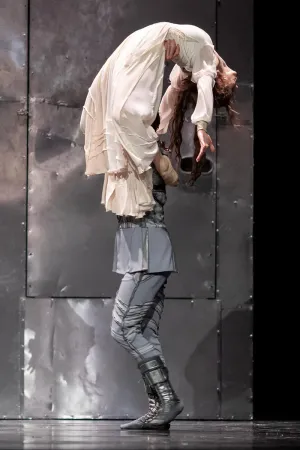

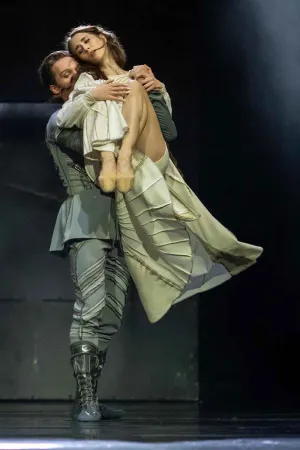

At a chivalrous tournament, Banović Strahinja, a hero from Banjska, competes and wins the prize - the hand of Angelia, the youngest daughter of Yug Bogdan, the eminent Serbian duke. The church ceremony and the wedding celebration that ensue, however, do not bring happiness to the newlyweds, who were not united by love, but by the socio-political convention of mutual strengthening of territories.

Banjska, Strahinja’s castle. On their wedding night, Angelia resists the consummation of the marriage, and Strahinja respectfully lets her go, which causes conflict between him and his mother, a true representative of that time, when a man used to take whatever he wanted without asking, even if it meant by force.

Strahinja goes to Kruševac, to the court of his in-laws, even though war is about to break out. Angelia and her mother-in-law clash over Angelia's resistance to Strahinja.

Suddenly, the Turkish army led by Vlah-Aliya breaks into the castle, destroying everybody and everything that stands in their way. Strahinja’s mother falls, knocked unconscious by a blow from a Turkish soldier, and Angelia, in a desperate attempt to save the others from bloodshed, seduces Vlah-Aliya, knowing that there is no life for her among the Serbs after such an act. She manages to distract the soldiers and leaves with Vlah-Aliya.

Strahinja's mother wakes up unaware of Angelia's sacrifice and curses her, and through the servant Milutin she sends a letter to Strahinja describing what happened.

The news about the misfortune that befell Banjska finds Strahinja in Kruševac, at the Yugović court, where he occupies himself with drinking and talking. He asks the Yugović brothers and Yug Bogdan for help, but they refuse to help him.

Disappointed, Strahinja sets off alone in search of Vlah-Aliya, who kidnapped his wife. On the way, he comes across an unexpected ally - an old dervish, his former prisoner whom he released from captivity. As a sign of gratitude, the Dervish shows Strahinja the way to Aliya's tent

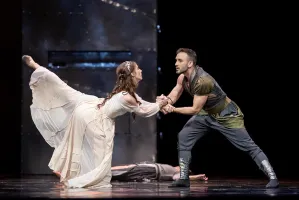

Vlah-Aliya's tent, bacchanalia. Vlah-Aliya and Angelia spend time together. With his gentle manners and conduct full of respect, Aliya seduces her and she gives herself to him.

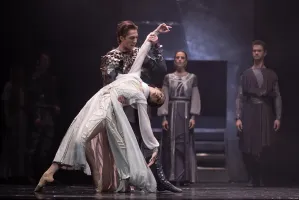

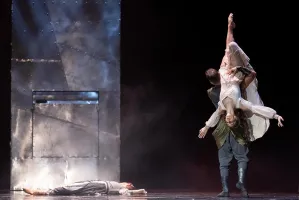

Strahinja finds Aliya and Angelia; he is overcome by wrath, and strikes a fight with Aliya. Angelia watches everything in silence and makes an unexpected decision - she chooses Vlah Aliya between two men. Overwhelmed by jealousy, Strahinja gets a surge of strength and wounds Aliya. On his deathbed, Aliya hands Strahinja a white scarf, a symbol of the sacrifice Angelia made when she decided to save the court and his mother, aware of the terrible consequences she will suffer.

Despite Angelia's noble cause, she is taken to court in Kruševac for instant trial, where her father and brothers disown her and sentence her to death. The execution of the verdict is interrupted by Strahinja who points out the hypocrisy of those who are ready to condemn, but unwilling to help when help is most needed.

Angelia and Strahinja develop affection for each other and they finally forgive each other, but war is on the horizon and Strahinja has to go into battle.

EPILOGUE: On the battlefield in Kosovo, Angelia finds the fatally wounded Strahinja and tends to his wounds. The story ends with an image of love, sacrifice and loss intertwined in the fate of a nation.

Đorđe Kosić